On the wheels of the street-cart movement, in an economic time by no means robust, a French Laundry disciple is attempting to reinvent a dining genre in a city called casual. (But really, Mr. Lee, no pressure.)

The dining room table of Corey Lee’s SoMa apartment is covered in porcelain. Just two months shy of the opening of his first restaurant, Benu, the former French Laundry chef de cuisine is preoccupied with the big picture—testing recipes for the menu, overseeing the construction of the dining room and supervising the installation of stoves, walk-in refrigerators and hood fans. But he’s also keenly focused on the small details, as evidenced by this tableware: samples of pieces he designed in collaboration with Korean porcelain company KwangJuYo, historic suppliers to Korean royals. When his restaurant finally opens this month, the 34-piece porcelain collection will be just one of thousands of carefully considered touches.

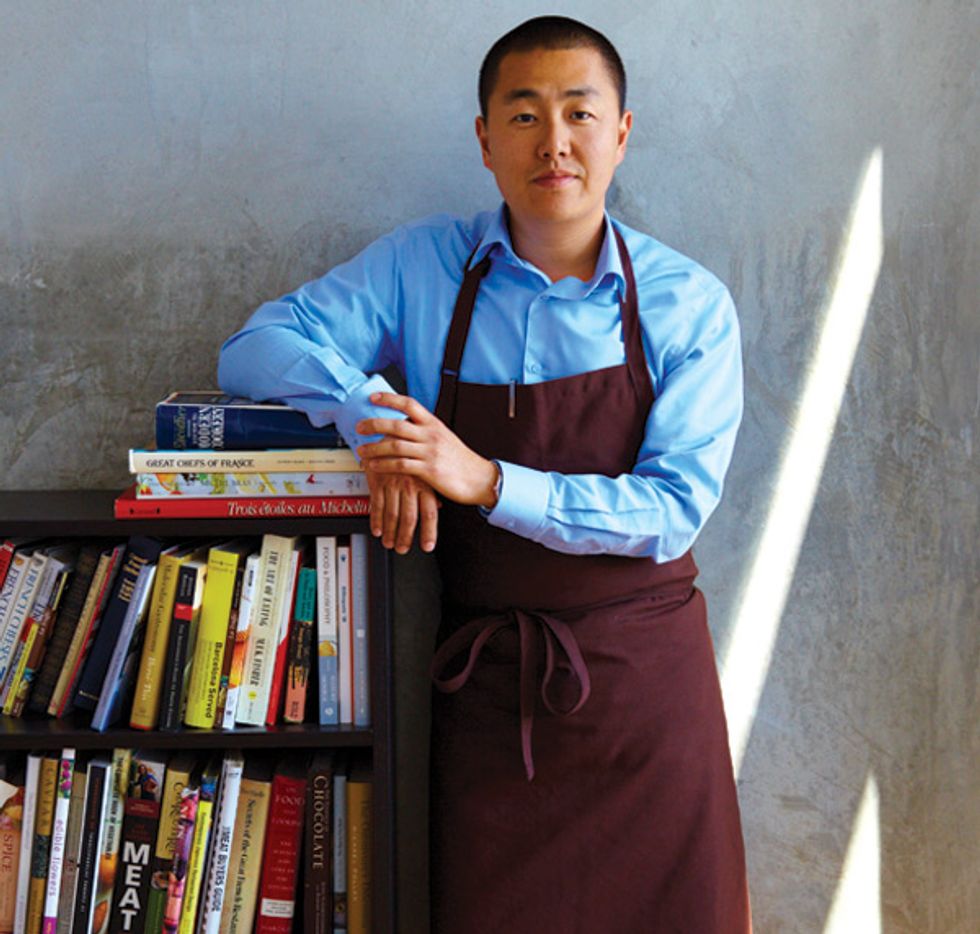

“There’s an enormous amount of risk involved,” says Lee, a quiet 32-year-old who was born in Seoul, Korea, and grew up in New York City. He worked for the last decade at French Laundry (and opened Per Se in 2001), and before that at seven three-star Michelin restaurants in England, France and the United States. “It’s an ambitious restaurant. But when you really believe in something, you have to go all the way.” He pauses, surveying the handmade wooden chocolate boxes and delicate porcelain cloches. “You can’t concede to something that’s less than you know you can do.”

Over the last several years, dining in San Francisco has become an increasingly casual affair. The rise of pop-up restaurants, burger joints and food carts all speak to a transformed landscape, one altered by the economy and shaped by young entrepreneurs eager to play out their one-off ideas. Projects like this have been, for the most part, critical darlings—earlier this year, Food & Wine magazine named Roy Choi, owner of the Los Angeles-based Kogi Korean barbecue truck best known for kalbi tacos, a “Best New Chef 2010.” But if Benu is any indication, fine dining—the very thing that scores of media outlets judged as “dead” two short years ago—is rising like a phoenix from the ashes. And here in the Bay Area, at least, fine dining isn’t simply being resurrected—it is being reimagined.

The very mention of fine dining in San Francisco evokes a golden age of mostly French, formal and buttoned-up restaurants that dominated the dining scene for much of the late ’80s and early ’90s. Fleur de Lys, La Folie and Aqua, along with Masa’s, the Dining Room at the Ritz-Carlton (and, later, Gary Danko and Michael Mina) shaped the food culture of the city as surely as the Beats shaped its literature and Harvey Milk shaped its politics. Historically, those restaurants—and versions of them in every major American city from Boston to Los Angeles—shared a luxurious commonality. “You had to have Frette linens, Riedel glasses, Bernardaud china,” says Laurent Manrique, the former chef of Aqua and current owner of Café de la Presse, who is currently at work on a restaurant in New York City. “That was the mode.”

Menus, too, shared a common language of luxury, peppered with caviar, lobster and later, foie gras. In the early days of fine dining, the identity and pedigree of the chef preparing your dinner wasn’t the point. Diners weren’t as concerned with a unique meal so much as they desired to have a high-level experience that was consistent in its class. Fleur de Lys chef-owner and Frenchman Hubert Keller says, “Thirty years ago it was French or nothing. The menus were all the same. Escargot, côte du boeuf. Today, the point of view of a particular chef is a large part of the reason a diner chooses a particular restaurant.” Thomas Keller, chef-owner of the French Laundry, agrees. “There’s been a shift,” he says. “We no longer have cultural food—French, Italian, Japanese—we have personal cuisine. People will go to Benu to try Corey’s food, just as they come to the French Laundry to have mine.”

But over the last 30 years, San Francisco restaurants have shifted away from French cuisine toward a more Mediterranean sensibility, with the rise of the mid-priced Italian neighborhood restaurant the surest symbol of all. As tastes in the city shifted, the economy tanked (more than once), and an ever-younger, ever-savvier dining public became the new arbiters of taste, the market for the classic, antiquated variety of fine dining began to shrink. “At a certain point,” says Daniel Patterson, chef-owner of Coi Restaurant, “we decided that our fine-dining restaurants should be casual, too. We have blurred all those lines.”

The blurring of those lines has had disastrous results for many of the old-guard, high-end restaurants nationwide. As The Wall Street Journal reported in December 2009, “The $8 billion fine-dining business—the category of meals costing $70 and up—has been the hardest-hit sector of the struggling restaurant industry. Nearly every city has lost one of its most famous restaurants in the past two years.”

San Francisco is no exception. Venerable old-timer Aqua—the one-time kitchen of Manrique, Mina and George Morrone—shuttered in April 2010 after 19 years. Hubert Keller sees innovation—not reinvention—as key to the longevity of Fleur de Lys. “We started shaking things up back in 1982,” he explains. “I wrote my menu in English, not French. I hired women as waitstaff. I was working within the confines of a fine-dining restaurant, but it wasn’t so stuffy.” But when I ask Hubert Keller—who has gone on to open several more casual restaurants, including Burger Bars in Las Vegas, St. Louis and San Francisco, if he thinks he would open another fine-dining restaurant in this city, he is quick to say no. “The cost becomes prohibitive. If it costs $5 or $6 million to build, you’ll never make a return. The answer is no. Not at that level.” Manrique, however, would like to open another fine-dining restaurant here, though he too recognizes the financial risk of doing so. “It would be the ultimate luxury, to open a place where I could be passionate and creative. Something personal. I think that’s the new fine dining.”

The presentation of the food—on porcelain Lee designed himself in conjuction with Korean company KwangJuYo—may say fine dining, but Lee plans to dispense with stuffy service, dress codes and other traditional hallmarks of the genre.

If the dining public has chosen to reject the trappings and tenets of fine dining, shouldn’t chefs and restaurateurs naturally evolve to meet customers’ desires? Doesn’t it make sense that casual concepts are on the rise? For many of the chefs I spoke with, it’s less about an unwillingness to reinvent fine dining and more about a fear that the rise in casual enterprises will eventually eradicate the craft of haute cuisine altogether.

“It’s a slippery slope,” says Patterson. “If we don’t have any high-end places, we lose our point of reference for classical technique. If chefs don’t have the training to execute ideas, the ideas don’t matter.” Ravi Kapur, the executive chef at the recently opened Prospect (the latest project from the Boulevard team), likens fine dining to haute couture, the twice-yearly high fashion that debuts on runways worldwide. “No, not everyone’s going to wear couture,” he says. “But eventually, those designs will make their way into Banana Republic.”

Chefs—particularly chefs here in California, where casualization in all arenas is a persistent threat—recognize that what diners want has shifted. “The trappings of fine dining are much less important to younger people. Hell, they’re much less important to me,” says Patterson. “We’re working on getting our servers out of suits.” When Mina reopens his eponymous restaurant this fall, relocating it from its current home in the Westin St. Francis to its new home in the former Aqua space, guests will have the option of ordering from both à la carte and prix-fixe menus, and the tables will be cloth-free. “I think diners want competent service and delicious food,” says Nancy Oakes, chef-owner of Boulevard and Prospect, “but they don’t want to sit at dinner for five hours anymore.”But if these details no longer matter to diners, if there isn’t, as Patterson put it, “something to hide behind,” the emphasis is returning once again to the food and the service. And if this is the case, it’s great news for diners in San Francisco. “That’s one thing that hasn’t changed: execution and product are still the most important elements of a fine-dining restaurant,” says Thomas Keller. I ask him if he’s surprised that Lee, his protégé, has chosen San Francisco as the site of his restaurant. “At the end of the day, I’m not surprised,” he says. “Twenty years ago New York cooks had the best technique, and San Francisco chefs had the best ingredients. I think Corey’s closing that gap. He has both exquisite product and solid execution.”

In closing that gap, Lee—and chefs like him, including Patterson, Commis chef James Syhabout and other innovators—are already changing the face of fine dining. “We’re making haute cuisine out of ingredients not typically associated with haute cuisine,” notes Patterson. “We know the rules, so now we can break them.” He notes that when his new restaurant, Plum, opens in late summer in Oakland (with chef Jeremy Fox, formerly of Ubuntu, at the helm) diners will find “hard rock, benches and an open kitchen. There will be lots of discipline in the food but energy in the room. This restaurant wouldn’t have existed 10 years ago.”

“I hear that people aren’t into fine dining anymore, and I just don’t think that’s true. People aren’t into good food? They aren’t into having a wonderful experience? I don’t believe it.” —Corey Lee, chef-owner of Benu

Of all the restaurant openings in San Francisco this year, Benu is the most hotly anticipated, owing to Lee’s experience at the French Laundry, arguably the most well-known American fine-dining restaurant in the world. The level of national attention that will be directed toward Benu is legion, meaning that from the moment the doors open, he’ll have something to prove. Should the resurgence of modern fine dining in San Francisco be possible, Lee appears to be the chef for the job. Despite Lee’s pedigreed porcelain, the young chef is not some bull-headed haute-cuisine loyalist. Benu won’t mimic the fine-dining experiences of yore, relying heavily on tropes and tradition. Rather, Lee wants it to express his modern vision of fine dining today.

“I am trying to pick and choose the most impactful things about fine dining,” he notes. “It’s the quality of the products, the technique and the care of the service. But none of that has to be fussy.” If Lee succeeds in melding classic technique with a modern sensibility (and bringing diners in the door), he may well usher in a welcome new era of fine dining in San Francisco. “I hear that people aren’t into fine dining anymore, and I just don’t think that’s true. People aren’t into good food? They aren’t into having a wonderful experience? I don’t believe it.” So marked is his disbelief, he’s banking his entire career on it.