In her debut memoir, Beer Money: A Memoir of Privilege and Loss (HarperCollins; out May 3), San Francisco writer Frances Stroh reveals what it was like to grow up as a member of Detroit’s Stroh’s Beer family, once in possession of the largest private beer fortune in America.

From Forbes 400 to nearly penniless in 16 years, the Stroh Brewery Company suffered a rapid decline during the 1980s and 1990s. In the face of financial ruin, Frances' family was also forced to deal with her father’s alcoholism, her brother’s drug addiction, and the slow decline of the once-great city of Detroit. Frances writes about it all with a brutal honesty and unsettling detail.

We caught up with Stroh before the San Francisco launch of the book next month.

7x7:What has been your family’s reaction to the book?

FS: My mother is the only family member who has read Beer Money cover to cover and she has been a huge ally, sharing galleys with her friends, building support, even reading the memoir out loud to a friend who has lost her sight. Other reactions from my extended family have been mixed; some have been very supportive, some haven’t. I hope when my family members read Beer Money they will understand it was written with respect and compassion for all involved.

What is the hardest part of writing a memoir?

Worrying about the feelings and reactions of family members is one of the toughest parts of writing a memoir because, no matter how carefully one handles the material, or how cognizant of tone, syntax, context, and perspective one tries to be, there will be family members who simply aren’t ready for the story to be told. A staggering level of sensitivity is required to protect their privacy and stick only to the details that are truly relevant to the story.

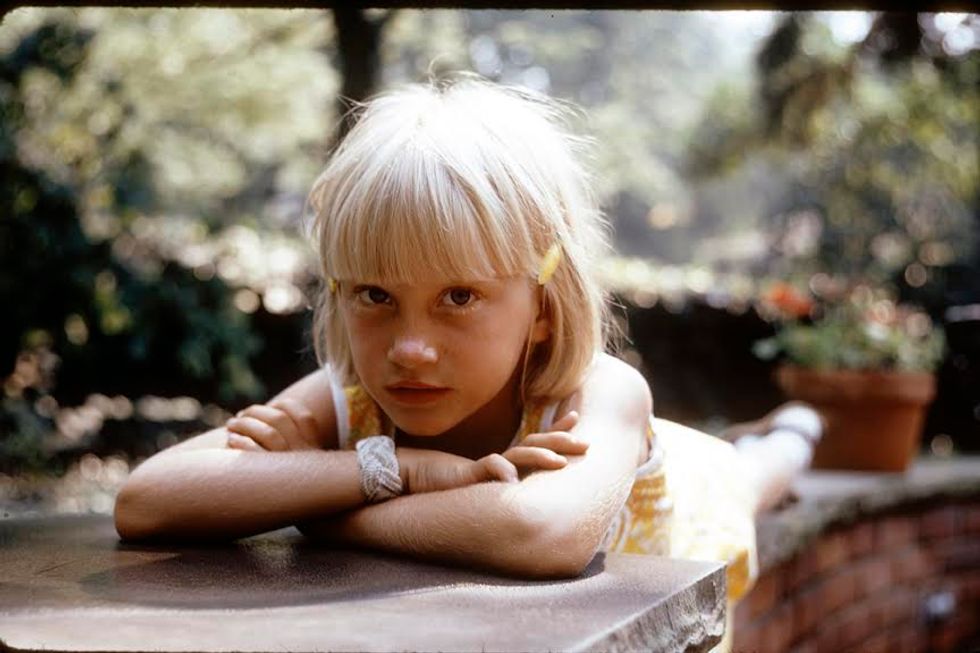

(A young Frances in Michigan; photo by Eric Stroh)

The family photos were a very poignant part of the book. How did you decide which ones to include?

My father’s photography played a huge role in our lives growing up not only because he photographed us so often, but also because his life’s work ended up in boxes in the attic. These dust-covered boxes came to represent, on an almost archetypal level, the failure of the frustrated artist that was our father. And so uncovering these images after 30-40 years has been profoundly redemptive, and a way to get his work out into the world, where it belongs. His images of the perfect American family combined with my truth-telling text creates a nice tension and amplifies the themes in the story. I see the combination as a wonderful creative collaboration between my father and me and the reason, I believe, that he left me his photographs in his will.

Did you save any of your father’s antiques collection?

I’m a minimalist and prefer a pared down living space. Most of the antiques and collections were sold, but I have a few pieces of furniture and a couple of paintings as keepsakes. I also have a vintage Leica camera my father gave me several years before he died. I still can’t figure out how to use it, but it reminds me of him.

You’ve dealt with a lot of tragedy in your life—what activities have helped you deal?

I lot of people deal with tragedy, and I don’t feel my life experiences are exceptional in this regard. I was always aware that there were people in the world suffering far more than I was, and very close to home, such as those who lost their jobs in Detroit when the automotive industry moved to the suburbs and abroad. No one from Grosse Pointe can pretend to have suffered the way people in Detroit have; these families know real loss like few Americans know it.

(A bottle of Stroh beer; photo courtesy of Stroh's Brewing Company)

Do you still go back to Detroit? What’s most different about the city today?

I go back to Detroit a couple of times a year and I always stay downtown because of the city’s vibrancy and explosive sense of potential. Detroit today is an epic story of self-reinvention, and a lifelong source of inspiration for me as an artist. My book ends in 2009 in a final scene where my brothers and I are driving through the city, observing the desolation—the defunct stoplight grid, the torched houses, the absence of any grocery store chains—and yet the artists are moving in and setting up shop in abandoned warehouses and storefronts. The Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit has just opened its doors, and the Detroit Institute of Arts has just expanded. Urban renewal groups are planting vegetables in open fields. It’s been incredibly gratifying to see these changes take place so rapidly even as I’ve been doing the final edits on the book, literally fulfilling the hope my brothers and I felt in those last pages set in 2009, when things looked so bleak for Detroit.

What do you see for Detroit’s future?

Detroit has a very bright future, and one with a much more diversified economy than in the past when the automakers and their supply chains composed the city’s main industry. With all the brainpower moving in now, the city is quickly becoming a vibrant urban center again—and a safe and creative place for children and adults to thrive. A portion of the proceeds from Beer Money is going directly to support the new 826 in Detroit, which will open its doors in October 2016.

The riverfront, in my opinion, is the next area to pop. The Detroit River has a beautifully maintained riverfront walkway and park—the Battery Park of Detroit—and yet just behind the posh walkway abandoned warehouses and weed-filled lots line the riverfront. It’s clear this special part of the city, which boasts stunning views across the river to Canada, is ripe for investment and development.

What made you shift from being a visual artist to a writer?

My artwork was very conceptual, and I was aware that this paralleled a certain detachment from emotions. I wanted my work to be more aligned with how I felt about the things that were happening in my life and within my own family. Much of my visual work used or referenced narrative in some way, so segueing, over time, into writing narrative was a way to extend the concerns in my visual work and to explore them more deeply.

What about San Francisco made you want to stay here?

Once I decided that my work would take the form of straight narrative, I realized I was already in one of the best cities in the world for a writer. The literary community in San Francisco is an extremely engaging, supportive environment. Being a member of the San Francisco Writer’s Grotto, I’m reminded every day of how many great writers we have in our city.

(The book cover; photo courtesy of Frances Stroh)

Do you drink beer?

Nine out of ten times I’ll take a beer over a glass of wine. I love Butte Creek IPA in the craft brew category, and Peroni—the PBR of Italy—when I want a crisp lager.

Favorite places in the city?

The bar at Hotel Rex, The Edinburgh Castle Pub, Delfina, Locanda, Seven Hills, and Tosca.

// See Stroh at Litquake’s Epicenter, May 9, 7:30pm; 2550 Mission St. (Mission), Get tickets here.