With this week’s BART strike, everything involving cars and car-related revenue has increased: Casual and formal carpool usage has increased; bridge toll revenue has increased; rental car revenue has increased; parking garage revenue has increased; parking meter revenue has increased; and with more drivers, (many unfamiliar with the ins and outs of City parking) and fewer spots available, parking ticket revenue and towed car revenue have increased.

As a result, parking frustration has increased, complaints have increased, emails to me have increased, and usage of VoicePark has increased. But, interestingly, because more people are connecting to the invisible web of SFPark sensors under each parking spot and connecting to them via VoicePark, the average amount of time that it has taken people to park this week has decreased. It’s cool to see technology having a positive effect on daily life.

That being said, the BART strike is impacting most everyone in the Bay Area somehow–many negatively–so while it is in everyone’s consciousness on some level, I thought I would share some of the info I have about BART, as it is an essential part of our overarching transportation web.

(Projector On)

(Lights Dim)

(Curtain Open)

BART is the fifth most-used transit rail system in the United States, behind New York, D.C., Chicago, and Boston. The system is made up of 44 stations, 104 miles of track, and 669 revenue cars, linking up five of the Bay Area's nine counties and the region's two largest airports.

The general theory of an underwater electric rail tube was first proposed in the early 1900s by Francis Smith, who was a guy who truly thought outside of the box. Case in point, in the late 1840s, when everyone and their brother was trying to find their fortunes mining for gold and silver, Francis made his fortune mining for borax (lots of dirty Levis to be washed, he figured). With his fortune, he became a civic visionary and builder. He didn’t convince people to build a transbay tube, but he did build the East Bay’s inter-urban Key Transit System which in the 1980s was sold and became known as AC Transit.

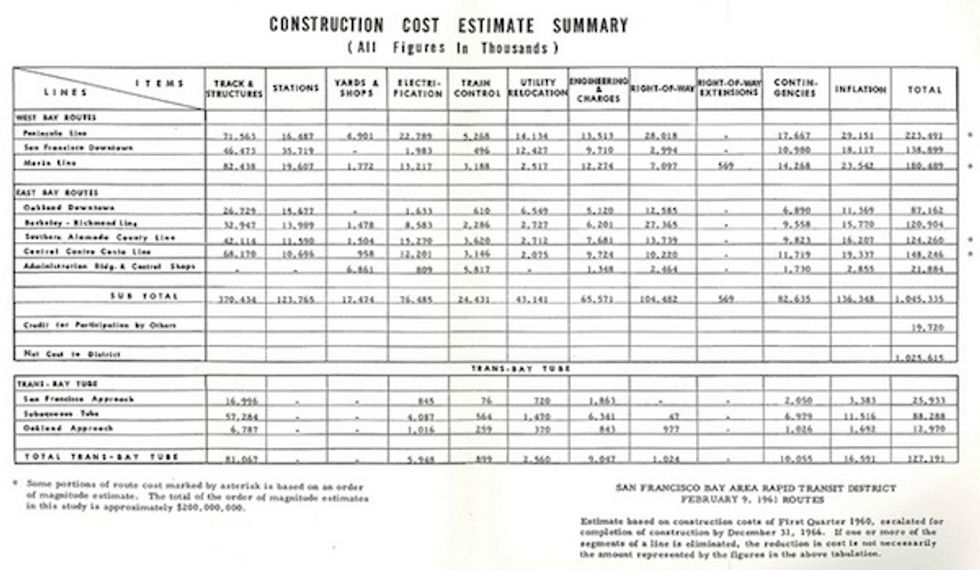

It took four decades for necessity to catch up with Francis’ insight about an electric transit tube, and as Bay Area business leaders began to become concerned with increased pre- and post-war migration to the Bay Area and its resulting exponential congestion, rough plans for the BART system and the TransBay tube began to be drawn as early as 1946. In 1951, California's legislature created the San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit Commission to study the Bay Area's long-term transportation needs. The commission approved plans for building BART in 1957.

The plans originally included five counties. Because Santa Clara County opted instead to concentrate on its Expressway System, that county was not included in the original BART District. In April 1962 San Mateo County made the decision to opt out also, citing high costs and concerns over shoppers leaving their county for stores in San Francisco. Marin County followed soon thereafter and opted out in May.

The BART plans were finally approved by the voters of the three remaining participating counties in November 1962, and construction began in the late 1960s, and it was all going to be paid for from toll revenue of the Bay Bridge.

photo by jeff fischer on Flickr

BART has been featured in a number of films including: The unfinished Transbay Tube, The Domino Principle, Predator 2, and The Pursuit of Happyness. BART played a smaller role in The Kite Runner, They Call Me MISTER Tibbs!, Eye for an Eye, and Kuffs, and in one episode of The Streets of San Francisco. Universal Studios uses a BART train in their underground earthquake simulator.

Now, for the nuts and bolts of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System.

Riders

Last fiscal year, 123 million total passenger trips were taken using BART. Ninety-five million riders on weekdays averaging 366,565 BART riders Monday through Friday and 28 million passenger trips on the weekends. New York by comparison has 2.5 billion riders per year, averaging about 8 million trips per day.

Trains

The third rail electric propulsion power is 1,000-volt DC electricity. Each car has 600 horsepower (one 150 horsepower motor per axle, and four motors per car). The cars' bodies are made of aluminum. Cars without cabs are 70' long and 75' long with a cab. Each car is 10'6" high, 10'6" wide, and has headroom of 6'9".

Lines

The A-line from Fremont to Lake Merritt, 23.8 miles

The M, W and Y-line from Oakland West to Millbrae is 27 miles

The R-line from Richmond to MacArthur is 10.6 miles

The C-line from Pittsburg/Bay Point to Rockridge is 29.3 miles

The L-line Dublin/Pleasanton to Bay Fair is 10 miles.

Tracks

Each track is 5’6” wide, compared to 4’8.5” for a standard track

37 miles of track travel through subways and tunnels

23 miles of track are aerial

44 miles of track are surface

Seating Capacity

The 668 revenue vehicles are comprised of 458 72-passenger cars and 230 64-passenger cars.

Speed

s reach 80 mph maximum, and 33 mph average (including 20-second station stops).

Station Equipment

: 300 ticket vending machines, 579 fare-gates, 168 add-fare machines, 80 bill-to-bill change machines (breaking $10 and $20 bills into $5 denominations).

Fares

BART fares are based on how far you travel. You can see exactly how much your trip will cost at the BART Fare Calculator.

Discounted Fares

Children 4 and under ride free (accompanied by an adult…it’s not a public mobile daycare facility) Children 5 through 12, seniors, and persons with disabilities are eligible for discounts.

Hats off to BART…and to borax. Let’s hope the strike is resolved soon.

David LaBua is a sustainable urban mobility consultant, author of Finding the Sweet Spot and founder of VoicePark.