“We were insiders, all three of us: Ernest Cole, Billy Monk, and me.” So begins documentary photographer David Goldblatt, your apparent guide to South Africa: In Apartheid and After at SFMOMA. “We each photographed from the inside what we most intimately knew,” he says.

The museum approached only Goldbatt about an exhibition; it was he who insisted on including the two other South African perspectives – those of Cole and Monk, neither of whom are living – in addition to his own white, middle class one.

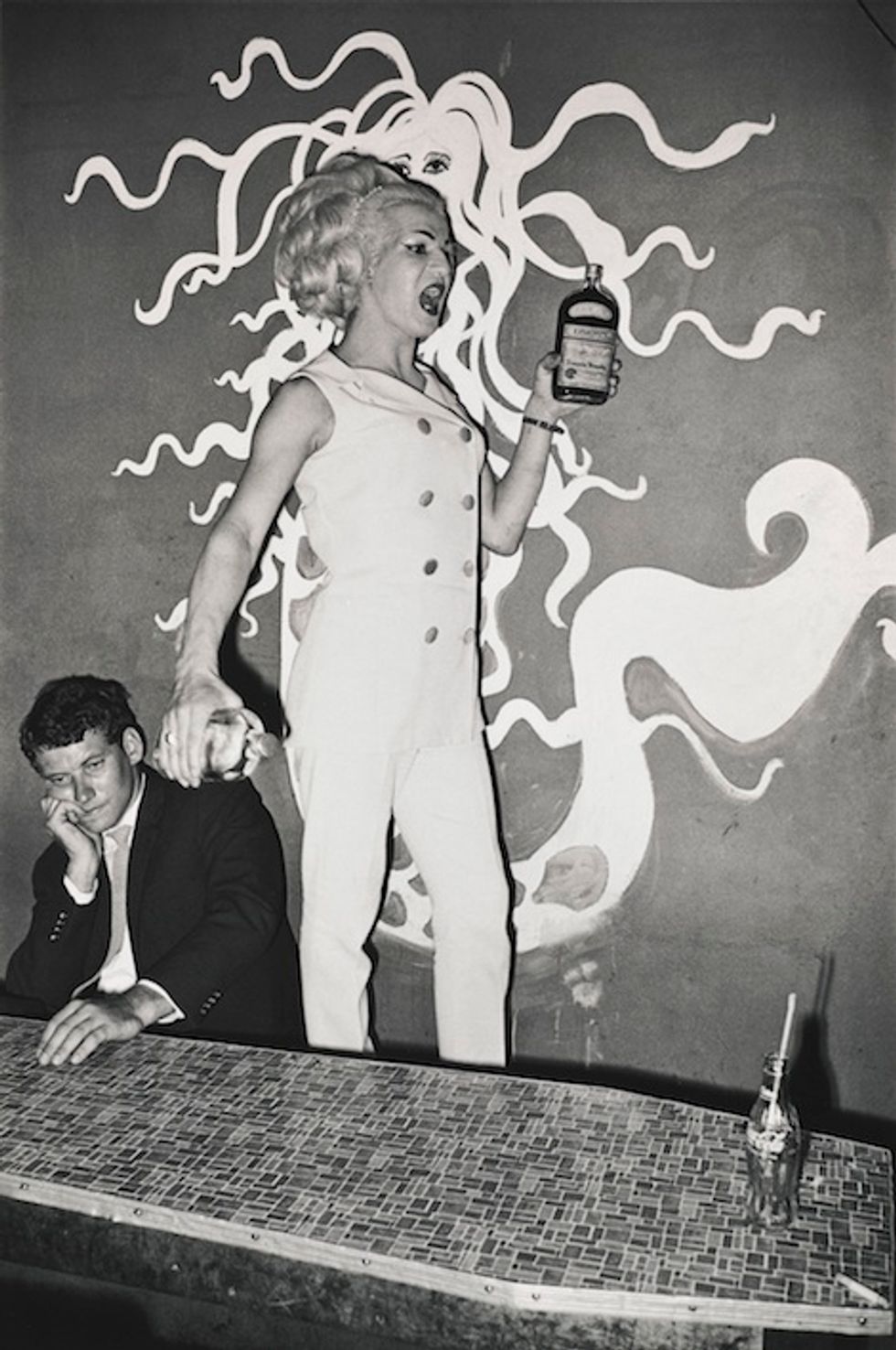

Cole, a photojournalist working in the 1960s, boldly committed himself to exposing the daily humiliations of and injustices against his people under apartheid. At age 26, he would go into exile to publish his bestselling (except in South Africa, where it was banned) book, House of Bondage. Monk, on the other hand, claimed no such formal position. He was a bouncer at a seedy Cape Town nightclub, Catacombs, where he would photograph clientele in hopes of selling them the prints. Because Catacombs was such an anomalous social zone – a hedonistic environment where “colored people” (read: People neither European nor black) were permitted to fraternize with whites – his snapshots would turn out to be of unanticipated significance.

Given the nature of what these men were insiders to, no balanced person would expect a particularly sunny set of pictures. Still, you may not be expecting a set as grim as this.

The condition of bondage that Cole captures is, as one would expect, revolting. The images we see in this section of the exhibition, from black miners being herded in the nude through humiliating medical inspections, to a panhandling child being slapped in the face by a white passerby, to the shantytown living conditions of segregated neighborhoods, crushingly capture an everyday experience that lasted almost half a century.

Billy Monk, The Catacombs, 21 November 1967, 1967, printed 2011; gelatin silver print; 15 x 10 in. (38.1 x 25.4 cm); Collection SFMOMA, Accessions Committee Fund purchase; © Estate of Billy Monk

Goldblatt’s photos of his middleclass white world are dreary in their own right. There are select cases of seeming quotidian bliss, as with the image of a beaming girl in a tutu en pointe on her front stoop, but generally we find images of a more odd, unsettling variety: A family that looks to be in the throes of shame and contrition upon the home visit of a local preacher; a boy who couldn’t be older then twelve, preparing to fight in a Town Hall amateur boxing ring, looking utterly terrified. At best, we have a mixed race church group “meeting to find ways of reducing the racial, cultural and class barriers that divide them” – a gentle thought, but of course inconsequential at a time when actual anti-apartheid activists were being sent to remote “banishment camps.”

Even Monk’s nightclub photographs, although presented as promising a glimpse of anomalous freedom, are actually more or less completely dismal. Most of the wrecked patrons seen in this hole (“seedy” does not begin to describe…) look to be about one brandy shot away from passing out or, if she is a woman, perhaps worse.

But it is Goldbatt’s “and After” that presents perhaps the most difficult works in the exhibition. It includes his soul-shattering “Ex-Offenders” series, portraits of recently released ex-convicts–the alleged perpetrators of rape, murder, torture and everything in between–at the scenes of their supposed crimes, along with text describing the criminal events in grisly detail as well as the personal histories of molestation, drug addiction and general destitution that seem to have precipitated them. Finally, we encounter a series of modern day desert landscapes -- dusty roads, the occasional shack in disrepair: An overwhelming sense of expansive nothingness. In the wake of Apartheid, is this what remains?

At risk of betraying my Americanness, it seems almost cruel to present a vision this bleak–not to museum visitors, who ought to have the stomach for it, but to South Africa itself, which must persevere in spite of its troubled past. Surely there are local cultures worth fostering, subcultures that have left the brandy-soaked misery of Catacombs behind. And yet, scarcely a single such breath of air makes its way into this selection of pictures (one counterexample does come to mind: a photograph by Cole of a festive local mine dance). If there is one glimmer of hope here, I suppose it is the existence of the exhibition itself–that these keen photographs, many of which seemed doomed to oblivion not long ago, may find wide audience.

South Africa in Apartheid and After runs through March 5 at SFMOMA, 151 Third Street