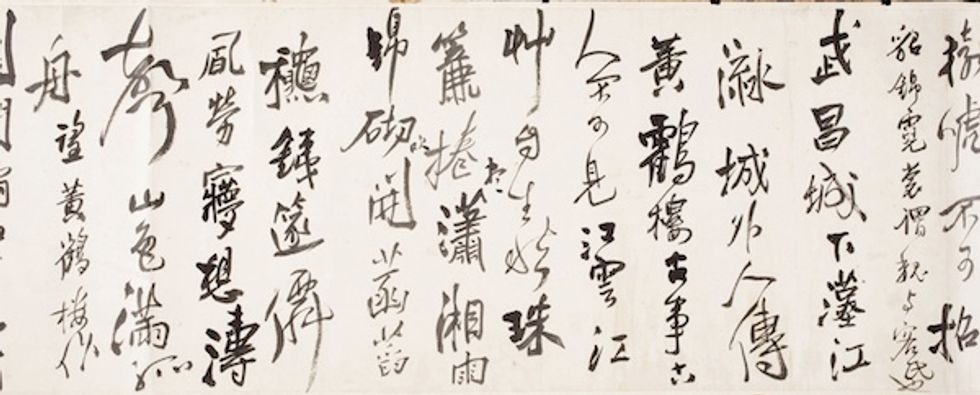

Two seemingly dissimilar museum exhibitions opened this week. Out of Character: Decoding Chinese Calligraphy at the Asian Art Museum marks the first major U.S. exhibition since 1999 of China’s most revered art form. Rudolph Nureyev: A Life in Dance at the De Young pays homage to a legendary ballet dancer and choreographer. Both, interestingly enough, put dance front and center.

Calligraphy does not open up to the Western viewer by itself. At least half of its impact, as poetry, is bound to be lost on those who cannot read Chinese. The other half, as a formally beautiful and astoundingly meticulous form of abstract painting, has the potential for more universal appreciation. A good curator, though, is required to pave the paths of entry.

Out of Character offers two such paths. One is American Abstract Expressionism. The Asian Art Museum borrowed three canvases, one Brice Marden, one Franz Kline and one Mark Tobey, from SFMOMA in order to draw a parallel between calligraphy and the familiar modern art movement. Or so one might expect. In what feels a little like a bait and switch, the exhibition winds up concluding that, while the American artists were each at least aware of and in some cases inspired by East Asian calligraphy, the respective art forms are in no way equivalent.

The other, more fruitful, point of entry is dance. Mesmerizing videos of calligraphy in progress make a compelling case for locating the written art form within a kinesthetic category. It is absolutely a dance of the wrist in which length of stroke, pressure and speed of ink application equate roughly to the domains of rhythm and style. Once this becomes clear, the masterpieces on display bloom.

Rudolf Nureyev and Noëlla Pontois in La Bayadère, Palais Garnier, 1974. Photograph by André Chino

Over at the De Young, meanwhile, Rudolph Nureyev is divided into two sections. The first is a fairly conventional biography, detailing through photographs, costumes and posters the career of the Soviet Union-born virtuoso who singlehandedly raised the standards for male ballet dancers, defiantly sought and achieved political asylum in the West, and ultimately died prematurely due to AIDS-related complications.

The second portion is a dark, hall-of-mirrors like chamber of reflective black paneling, floor-to-ceiling woven veils bearing images or projected video of Nureyev’s choreography, and lots of costumes. Video is the exhibition’s strong suit; it is best at capturing Nureyev’s remarkable skill and personal vitality. The costumes, in contrast, are frankly rather ghostly. The exhibition cursorily asserts the importance of costumery to the art form as a whole but does not really follow through in explicating this claim.

In consequence, for all its emblazoning of Nureyev quotes like “You live as long as you dance” and “I’m really alive when I’m on stage,” the exhibition comes off feeling a little too much like a headstone followed by a tomb.

Out of Character: Decoding Chinese Calligraphy runs through January 13 at the Asian Art Museum, 200 Larkin Street. Rudolph Nureyev: A Life in Dance runs through February 17 at the De Young Museum, 50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive.

Recommended pairing: Dance Rehearsal: Karen Kilimnik’s World of Ballet and Theatre runs through December 9 at Mills College Art Museum, 5000 Macarthur Blvd., Oakland