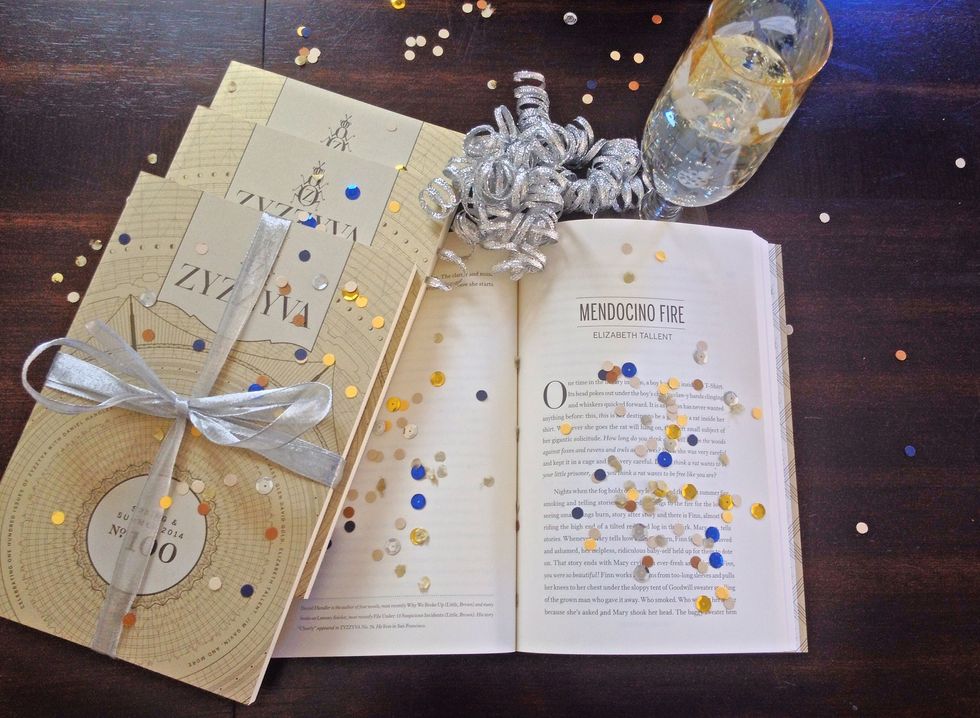

Since 1985, San Francisco-based literary journal ZYZZYVA has been promoting the best and brightest of West Coast writers and artists, publishing the work of everyone from Haruki Murakami to Sherman Alexie to Raymond Carver. The journal just issued their 100th edition, and the path to that achievement hasn't always been easy. "It's a rare thing for an independent non-profit literary journal to be around long enough to produce 100 issues," says Oscar Villalon, who edits ZYZZYVA alongside Laura Cogan. "It's a testament, I think, to the vitality of the journal's mission of representing West Coast writers in print."

The 100th issue contains work from some of the Bay Area's best writers, including Rebecca Solnit, Daniel Handler, Kay Ryan, Robert Hass and Dan Alter, Paul Madonna, Jonathon Keats, Katie Crouch, Elizabeth Tallent, and Austin Smith. On May 8, a special fundraiser celebrating the 100th issue at the California Historical Society will feature Hass, Handler, Po Bronson, and Erika Recordon.

For a taste of what's inside the issue, here's an excerpt from Bay Area-based writer Glen David Gold (Carter Beats the Devil, Sunnyside). The piece, "The Plush Cocoon," which appears in full in the journal, is itself an excerpt from Gold's upcoming memoir.

"The Plush Cocoon," by Glen David Gold

My mother grew up in London during the war. She told me that bombs sometimes fell on her playground, and this was one of the only things I knew about her youth. She married an American G.I., moved to Hollywood, divorced, and met my father, and she told those stories with leisure and nuance. It was as if everything that had happened to her in England was chaos, fog, and switchback trails overgrown with nettles. Everything in America was instead an easy map—obstacles met and overcome, culminating, she would have me know, in my birth.

I grew up in Corona del Mar, south of Los Angeles, in a house that faced the sunsets. I can’t imagine how different it was for my mother from her childhood. When she became a citizen, one of her graduating group said that in his home country, Switzerland, geography was a good metaphor for friendships. Upon entering Switzerland, or a family’s living room there, immediate, unscalable-looking mountains confronted you. In a number of years, perhaps a lifetime, you might learn of one or two passes that would allow you entry into a Swiss person’s heart.

California, on the other hand, said the Swiss, was all beach. The moment you arrived, you could walk shoulder to shoulder with the locals, and you were made to feel welcome, even if you didn’t feel ready for it. “But never mind,” he added. “Because when you know the Californians after years and years of being on the beach with them, guess what? Mountains. You’ll never get over them.”

My mother didn’t fit in. She looked like she should—long blond hair, slender body, kind blue eyes, skin that tanned easily—but her body knew otherwise. Before she’d moved to America she hadn’t known what a sunburn was. She had a modest two-piece swimsuit of pale blue, insulated with many layers of material between its exterior and where it touched her body. Its bottom piece reached above her navel, the better to cover a mysterious curved scar on her back that, when I was very young, I would touch with my fingertips to try to understand the different ways skin could feel. When she was four years old, she’d been in the hospital for many months. No one had told her why. When she came to the United States, a doctor saw the scar and asked her why she’d had a kidney removed.

She didn’t know she was missing a kidney.

How disconcerting it must have been then to hold in her mind both her gothic childhood and her present life of coastal breezes, sunglasses, money in the bank, her own swimming pool, going barefoot at cocktail parties, how even in wintertime her friends would pick fruit from their back yards, make bowls of sangria and greet her at their front doors with a happy Mi casa es su casa.

Because it was Southern California we took long drives almost every day. I learned that when we went by a pasture, if you relaxed your eyes and let the fence posts rush by, the tiny flickers of the sights beyond would resolve into glimpses of the farm. That’s what it was like with my mother’s life.

She sewed clothing for me. She made me tuna melts for lunch. When I couldn’t sleep, she sat on my bed and sang “Moon River.” She read up on ESP and decided she had it. I used to lie on my bed and try to send out brain waves to my mother. SOS! Sometimes, on a different day, she would come into my room and ask if I’d just been “calling” her, and I always said, Yes, and she would nod, significantly, admitting to a seasonal wind she could count on.

I was hers then. I loved my father but I belonged to my mother. I knew a look on her face so well I would sometimes lie awake at nights thinking about it. Something weighed on her, something that separated her from the present. Under big canvas reflective hats, zinc oxide on our noses, sunscreen on our shoulders, we hiked at the beach in our swimsuits, exploring the tide pools, tipping our big toes into sea anemones for the pleasure of it, and something was wrong. When I learned how to swim beneath an approaching swell, I popped up safely, in triumph, and yet my mother’s concerned eye fell on me with a weight I didn’t understand. Back on shore, she reached for my hand as if there were a border crossing only she could see and there were armed guards whose graces she would have to court with politeness and fear. Her silent gaze, if it could be translated, said, You don’t know what you escaped. And, because her worry lingered,

It might come back.

— From "The Plush Cocoon" by Glen David Gold

ZYZZYVA's 100th issue is available at indie bookstores around town, including Green Apple Books, the Booksmith, and City Lights. You can also pick up a copy ($14) on their website.