Anyone who’s taken a contemporary art history course in the past thirty years has probably seen a sampling of Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills – they have become as much a fixture in the artistic canon as Manet’s Olympia. For the first time ever, all sixty-nine of them are in California. They compose roughly half of a critically acclaimed Sherman retrospective that has just arrived from New York at SFMOMA. People are seriously excited. Half of them have no idea what they are in for.

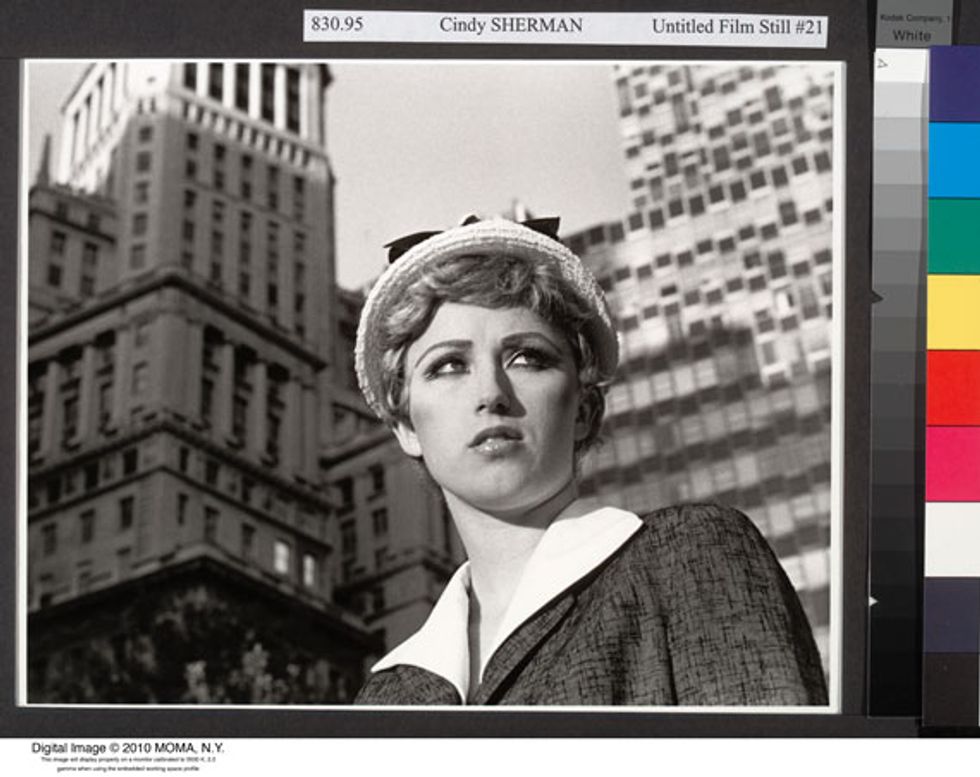

The black and white Stills are meant to look like publicity shots from a selection of nonexistent but entirely imaginable films. In each, Sherman strikes the pose of an immediately recognizable female “type,” in effect cataloguing the limited list of feminine identities that 60s and 70s cinema endlessly recycled – the blonde bombshell, the seedy vamp, the suburban seductress, the woman in distress, the nervous wreck.

The opportunity to take in all of them at once is not to be passed up. Splayed across 3 walls, in total they reveal Sherman’s one-in-a-million talent for image construction. She knows how much meaning, albeit formulaic, can be transmitted by a particular expression, manner of dress, the way one clutches a carton of eggs. With Film Stills, Sherman lifted the veil from the modern machinery of identity construction, or at least ruffled it, and all with a sense of playful fun.

People are less familiar with Sherman’s subsequent work, from the early 1980s through the present. Larger and in vivid color, the works continue to explore the theme of femininity, image construction and personal identity. Their tone, however, quickly drops the girlish “dress-up” quality of the artist’s art school days. More concrete adversaries emerge. Some of the photographs at times become very dark indeed.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #21. 1978; gelatin silver print; 7 1/2 x 9 1/2" (19.1 x 24.1 cm); The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Horace W. Goldsmith Fund through Robert B. Menschel; © 2012 Cindy Sherman

One of Sherman’s later triumphs has been her fashion shots, many of which were commissioned by unsuspecting haute couture houses like Balenciaga and Marc Jacobs. In these photographs, Sherman represents what the exhibition refers to as “fashion victims” – steely fashion editors, PR mavens, wannabe fashionistas. Accoutered in designer clothing, Sherman becomes women who look delirious, angry, haggard, bloodshot and decidedly under the influence of gravity, in effect subverting the usual industry image codes of glamour, levity and grace, and laying bare fashion’s unspoken role in communicating gender, class and other aspects of identity.

The next gallery, labeled “grotesque,” will prove a challenge for museum visitors. Sherman slips out of the picture frame entirely here, positioning medical prosthetics as stand-ins. Inflamed genitalia, pubic hair, blood and confetti-speckled vomit abound. In one indelible work, a witch-like hag births what looks like a string of thick black sausage links. Aiming for more than mere shock value, these works explore issues of bodily representation and the abject that other artists, working in a cultural milieu of censorship, conservatism and the AIDS specter, were not able to risk producing. To be sure, Sherman was also giving the finger to the art market, where her signature was already very valuable. “You want me, but you can’t have me because you don’t have the balls to purchase this,” she seemed to say.

As the roughly chronological exhibition rounds the turn of the 21st century, the Untitled Film Stills seem to belong to a distant past. Gone are the days of Hollywood bombshells and women in distress. Sherman’s latest work represents a new set of female types in the media crosshairs – the would-be stars whose careers progress no further than a bit part in a soap opera or a humiliating American Idol audition, the orange-skinned East Coast party girls who drink themselves sick on reality TV, the older women who cling to youth with plastic surgery and pancake makeup. It seems the world that the Film Stills prophesied, in which media representation and “reality” have irrevocably conflated, has arrived.

These final series leave a bitter taste. Unlike the women in Film Stills, Sherman’s subjects here are not merely embodied “types” but potentially real people – victims of the identity mechanisms that she has made a career of exploring. Moreover, they don’t need Sherman to make them look ridiculous; with the ever-present Reality TV camera aimed at them, they more than accomplish this themselves. The photographs ring of unnecessary satire, maybe even laced with a bit of cruelty. In retrospect, perhaps they betray a lack of empathy that had always been there.

Cindy Sherman runs through October 8 at SFMOMA, 151 Third Street