Between 1936 and 1951, a group of zealous New York photographers known as the Photo League set out to document life on the city streets. What they ended up capturing, however, was far larger. Pointing dogged, unaverted lenses at life during the Great Depression, World War II and the triumphant but troublingly conservative postwar period, the league effectively captured the tumultuous making of the America most of us have known.

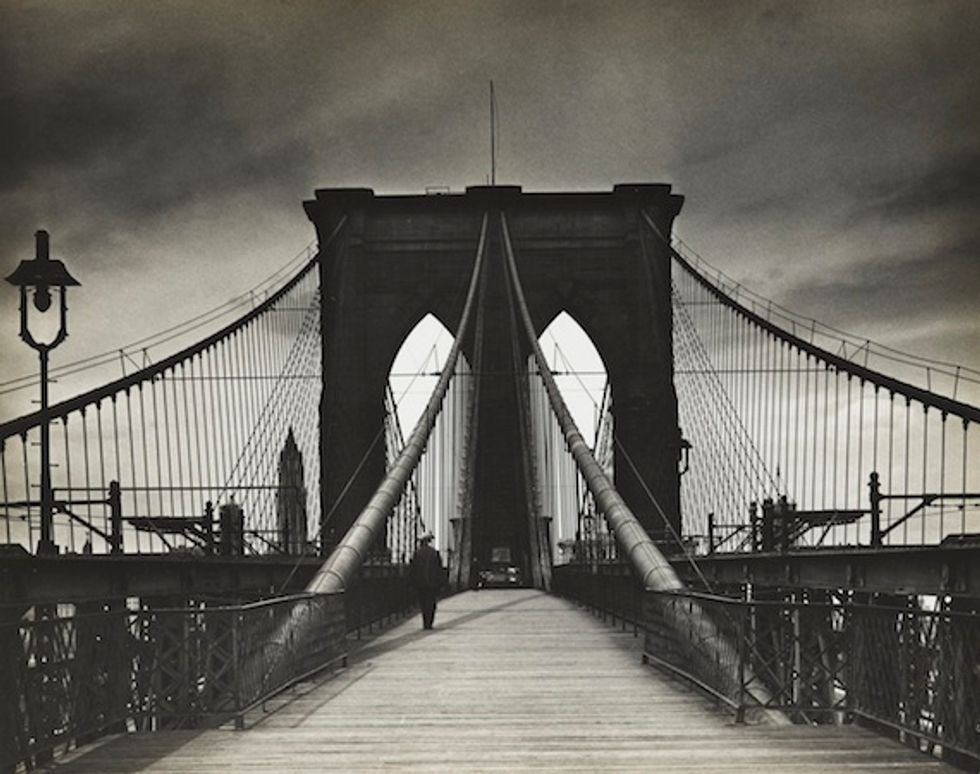

The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936 – 1951, now at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, presents a comprehensive survey of the League’s work through 150 photographs ranging from the gritty to the effervescent, the stark to the poetic. Not only does The Radical Camera open up a lost, sepia-tone world of sooty streets, arching steel constructions and various forms of social illness, it tells the story of a novelty device becoming a force of subversive social activism and, eventually, art.

While the League claimed several dozen members, many of them now major names in documentary photography, The Radical Camera rightly portrays the cooperative as a single functioning organism greater than the sum of its constituent parts. Most of its members came from similar backgrounds (first generation American Jews) and held similar political views (socialist). They agreed collectively on their mission (to objectively and politically capture the life of the city’s working class), and only gradually came to tolerate the notion of indulging individual subjectivities in the image-making process.

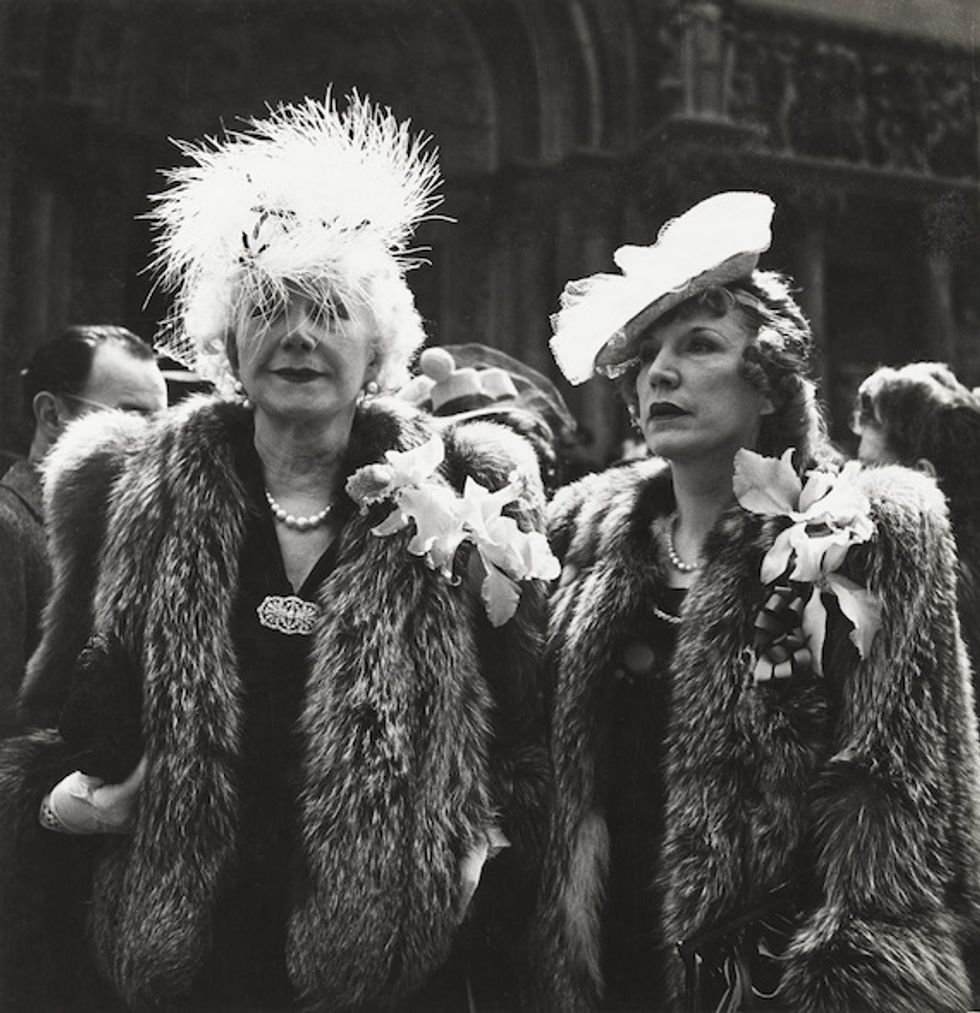

Elizabeth Timberman, Easter Sunday, 1944. Gelatin silver print, 10½ x 10¼ in. The Jewish Museum, New York, Purchase: Photography Acquisitions Committee Fund. The Radical Camera: New York's Photo League, 1936–1951. On view October 11, 2012–January 21, 2013. Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco.

This development from a staunchly journalistic to a more artistic attitude is one of the exhibition’s more interesting arcs. Amid the many straightforward, though beautiful, shots, one finds increasingly more photographs that play with formal composition and cropping, make retroactive alterations such as blurring to convey the feeling of a scene, and introduce provocative ambiguities. The exhibition concludes with a large-scale print by Photo League School director Sid Grossman, depicting a group of frenzied bird’s diving into shimmering water. Captured from directly above, the vertiginous work could hang alongside abstract expressionist canvases. “The transmutation of the documentary mode into an experimental, personal vision” had blossomed, ripe for the subsequent generation to pick up.

Still more interesting, though, is the tragic story of the League itself. Amid the triumphant elation of the prosperous postwar period, the Photo League found itself facing a wave of vicious conservatism, manifested in McCarthyism and anti-Semitic Red Scare hysteria. Needless to say, the League’s socialist leanings would come to haunt it. In 1947, the attorney general blacklisted the League as “totalitarian, fascist, communist or subversive.” Compelled to ease off the representations of class and racial politics that had been its primary concern from the outset, the League re-branded as the “Center for American Photography,” shifting focus to aesthetic questions. But it was too late. Ostracized, the group disbanded in 1951 – “a casualty of the Cold War,” the exhibition concludes.

In a politically charged moment such as ours, the story of the Photo League is one worth remembering.

The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936 – 1951 runs through January 21 at the Contemporary Jewish Museum, 736 Mission Street.