I have heard it said that San Francisco is “the land of fruits, nuts, and veggies.” And we like it that way, thank you very much. In a city that supports a live-and-let-live ethos, San Franciscans don’t just tolerate—we celebrate—diversity and forward thinking. Here, we are pioneers in sustainable living, technology, and culinary innovation. Women have prominent spots in politics and in business. We support medical marijuana and provide safe escort for naked cyclists. Many of our charities are even bolstered by fierce drag queen nuns.

And of course, SF is the country’s mecca for LGBT people and their families, with 30 percent of the state’s gay population calling the Bay Area home. In February 2004, in a renegade move that bypassed state law, then-Mayor Gavin Newsom made SF the first U.S. city to issue marriage licenses to LGBT couples. Though a few months later Massachusetts would become the first state to legalize marriage equality, Newsom stated it for the record: San Francisco would be a trailblazer in the civil rights movement of our time.

For SF residents—mostly liberal-leaning creative thinkers—the city is a constant source of pride and has a quality of life you’d be hard-pressed to match anywhere else. So sure of this are we that it is sometimes easy to forget: We live in a 49-square-mile bubble. That is, we did until Proposition 8 came along—with its busloads of anti-equality activists hailing from Fresno to Utah—to rain on our big gay parade.

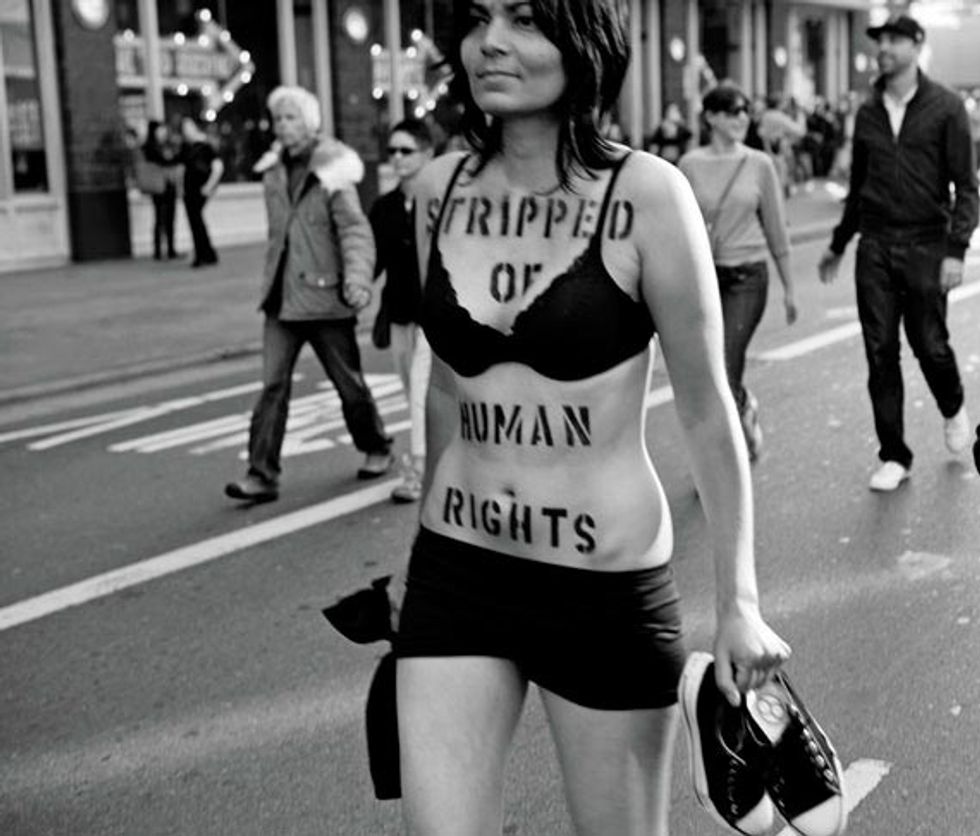

Even here—or, perhaps, especially here—the fight for marriage equality has been a roller coaster from the word “go,” and families have been both made and broken by it. The Newsom marriages were quickly revoked, compelling many couples into the limelight as poster children for a movement. “Don’t force divorce” became a common slogan. And those who had been given, and then stripped of, such a basic human right were then obligated to lead the charge. Some of those couples didn’t make it. Marriage, after all, is tough enough without spending your free time fighting for it in the face of public adversity.

It was four years ago that the California Supreme Court overturned the ban on same-sex marriage. On June 16, 2008, LGBT couples began tying the knot across the state. Pride that year was bittersweet: What should have been the most celebratory moment in the community’s history was overshadowed by Prop 8, the impending ballot initiative designed to make marriage equality subject to popular vote.

Among those couples who had survived the storm thus far, many opted not to marry again when the opportunity arose. The upcoming vote on Prop 8 overshadowed our four-and-a-half month window of equality. The future was too uncertain. Many, understandably, just couldn’t stomach another go.

When Prop 8 passed on Nov. 4, 2008, it became clear that San Francisco, fabulous and progressive as it may be, is not immune to the prejudice that dominates much of our state and country. We aren’t immune to ignorance and, yes, hatred directed at LGBT people. (Even as I write this now, two gay men were recent victims of a hate crime in the Castro.) On Nov. 4, voters put the kibosh on California’s same-sex marriages, which were already at 18,000 and counting. (My partner, Frankie, and I are among those limited-edition marriages that remain legal to this day.) The state’s chickens, however, won a major victory that night: Proposition 2, which passed by 63 percent, protected the basic rights of farm animals. The next day, at a protest at City Hall, a sign read: Chickens 1, Gays 0.

“How could this happen here?” was the question on everyone’s lips. Here, the city where Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon founded the country’s first lesbian rights organization, the Daughters of Bilitis, in 1955; here, the city that launched the Alice B. Toklas Democratic Club to gain LGBT support among politicians in 1971; here, the city that helped elect Harvey Milk, California’s first openly gay man in public office, in 1978; here, where Martin and Lyon became San Francisco’s first legally wed LGBT couple (on June 16, 2008) after 56 years together.

Of course, the passing of Proposition 8 didn’t happen here. San Francisco voters rejected Prop 8 by 75.2 percent, the biggest margin in the state. It is widely believed that we lost this fight because San Franciscans failed to look outside the bubble—we missed the opportunity to take San Francisco and everything it stands for out to the rest of the state.

In the bubble, we were so confident of our righteousness that we barely left the Castro in the run-up to the ’08 election. Meanwhile, if you headed an hour east into Contra Costa County or a few hours south to the Sierras, you would find those yellow “Yes on 8” signs, with the desperate slogan “Restore Marriage.” Even a jaunt to Napa would show that opposition was all around us (in Napa County, a mere 55 percent voted against Prop 8). Los Angeles, home to Hollywood of all places, voted for the ban on equal marriage.

Instead of sending our own busloads on the campaign trail—where groups like the National Organization for Marriage (NOM) successfully degraded LGBT relationships—we preached to the choir. The national dialogue around marriage equality ignited here, thanks to Newsom, and we were so sure it would end here. It didn’t then. But it still might.

On Feb. 7, 2012, the SF-based Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled Prop 8 unconstitutional in the landmark case Perry v. Brown, helmed on our side by prominent lawyers—Ted Olson, the former U.S. solicitor general under George W. Bush, and David Boies, who represented Al Gore in 2000’s Bush v. Gore. On Feb. 21, Prop 8 supporters appealed to the Ninth Circuit. If the court refuses to hear their case again, some believe it could go to the United States Supreme Court. Should it, the rest, as they say, would be history—whichever way it swings.

Some legal analysts doubt the Supreme Court will hear this case due to the language of the Ninth Circuit ruling, which limited its scope to California. According to Loyola law professor Douglas NeJaime, “The Ninth Circuit decided the case in a way that would allow the Supreme Court to affirm without having to significantly expand on its existing jurisprudence and without having to rule on marriage for same-sex couples on a national scale.”

Even our lawyers are divided about the potential outcome. Boies concedes the ruling may lessen the likelihood of the Supreme Court taking the case. Olson—who has argued 58 cases before the Supreme Court—is more optimistic, saying, “This is a very significant milepost on the way to equality in this country.”

Either way, there can be no doubt that San Francisco is a landmark along the road to marriage equality, propelling the movement to history-making momentum. Since those Newsom-sanctioned vows that were heard around the world in 2004, marriage equality has become law in six U.S. states: Iowa, Connecticut, New York, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts, as well as in Washington D.C. Both Maryland and Washington State have signed laws in favor of marriage equality, though voter referendums threaten to derail the progress this year. Ten countries—including South Africa, Argentina, and heavily Catholic Spain—also recognize marriages for LGBT couples.

The very same night that California voted against civil rights for LGBT people, Americans voted for a president who promised change. President Obama repealed Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, and on May 9, in an interview with ABC News, Obama affirmed, “I think same sex couples should be able to get married...It’s the Golden Rule: Treat others the way you would want to be treated.”

Still, in the aftermath of Prop 8, an estimated 15 percent of SF residents await the validation of equality, living in the gray area between our now unconstitutional ban on same-sex marriage and a seemingly indefinite court-ordered stay on marriages. Whatever happens, the tipping point is near. When it does, San Francisco will know that we were, once again, ahead of the curve. And this San Franciscan will get on the bus to Fresno.

This article was published in 7x7's June issue. Click here to subscribe.