In the summer of ’69, while the average red-blooded American male not soldiering in Vietnam was, as popular music tells us, playing a five-and-dime six-string and wooing a girl standing on her mama’s porch, Lee Brooks was experiencing his first LSD flashes. For someone who hails from the dusty ag town of Bakersfield, CA, the psychedelic episodes were life-changers. “Once I was lying on the floor of a dark room barely lit with a single flickering candle,” recalls the now-74-year-old from his home in Sea Ranch. “That little point of light became God’s mouth, and it said to me, ‘Find peace in chaos.’”

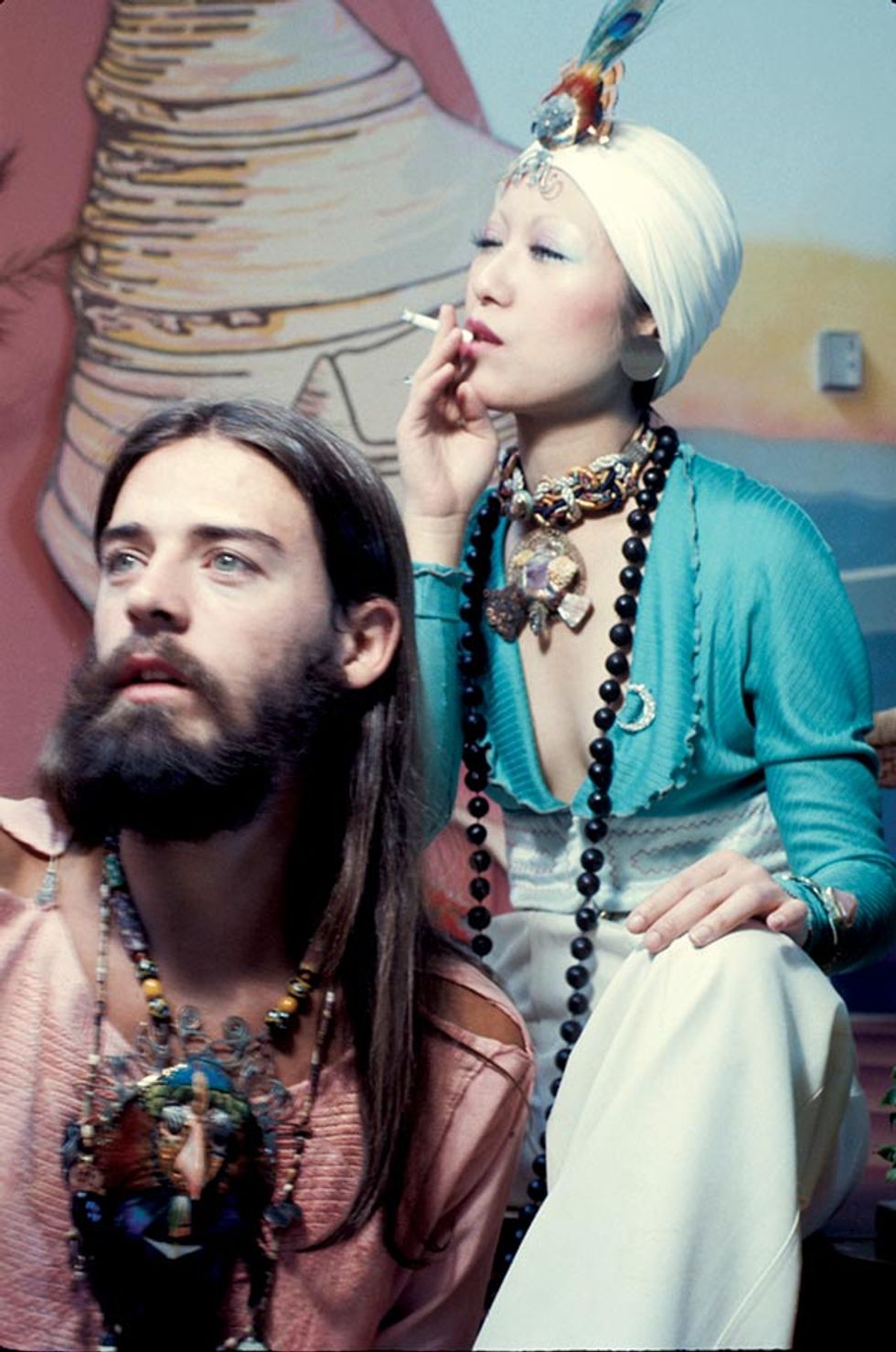

The profound message would unwittingly inspire his future artistic endeavors. In 1970, Brooks, along with his life partner and creative collaborator, Alex Maté, cofounded Alex & Lee, a San Francisco–based jewelry line of theatrical tribal-inspired medallions made of feathers, chipped seashells, crystals, driftwood, bone, and other objects found in nature. “We started to design jewelry for fun, as a way to vibe positive, creative energy into such a tumultuous time,” says Brooks of his interpretation of the divine dispatch.

As it turns out, he and Maté, who died in 1992, weren’t alone in their pursuit. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, many counterculturists eschewed participation in political rallies for the quiet sanctuary of their homes or communes, where they channeled their artistic talents into handcrafted fashion and design. The folksy, uninhibited style—think patches galore, wild embroidery, and gutsy mash-ups of materials and patterns—would forevermore be regarded in voguish and fringe circles as “funk and flash.”

Fiber artist Alexandra Hart coined the term in 1974 when she wrote a book called Native Funk & Flash (Scrimshaw Press), about the network of more than 80 Northern California artisans who were defining the aesthetic of a generation by finding their own creative—and often psychedelicized—route to inner peace.

For Hart, whose funk and flash endeavors began with the elaborate embroidery of mishmashed motifs onto clothing—flowers, crescent moons, rainbows—much equanimity was gained through the physical act of sewing. “There’s nothing like it to calm the mind,” says the Sebastopol resident. Her longtime friend, self-taught shoemaker Mickey McGowan (aka the Apple Cobbler), known during the free love decade for his kitschy brocade boots stacked with four-inch-thick rainbow-colored foam soles, concurs. “I couldn’t control Vietnam. I couldn’t control the Bay Area’s volatile environment. So I just quietly made things,” he says. “Sometimes the only way to ride out the storm is to sit peacefully in the eye of it.”

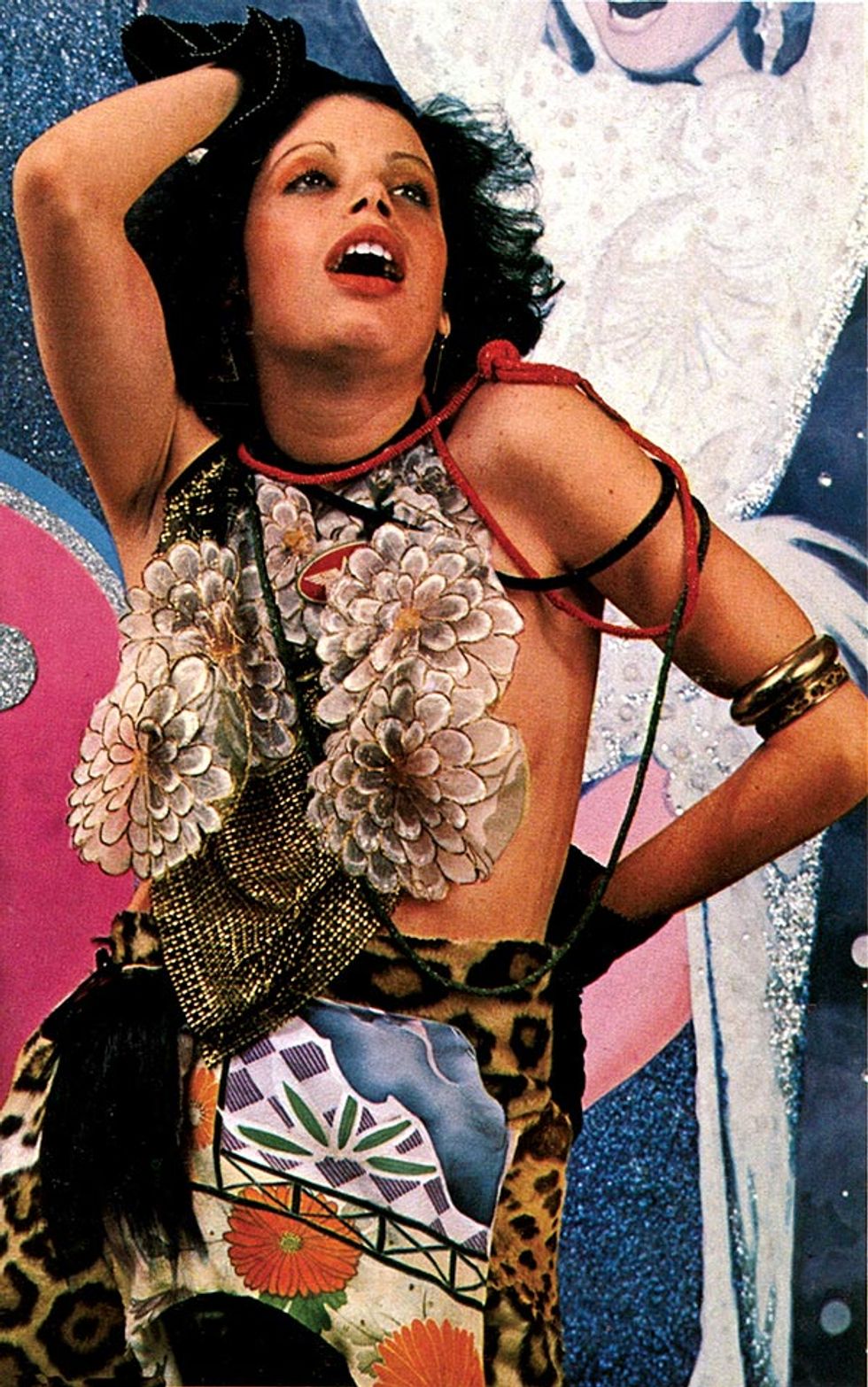

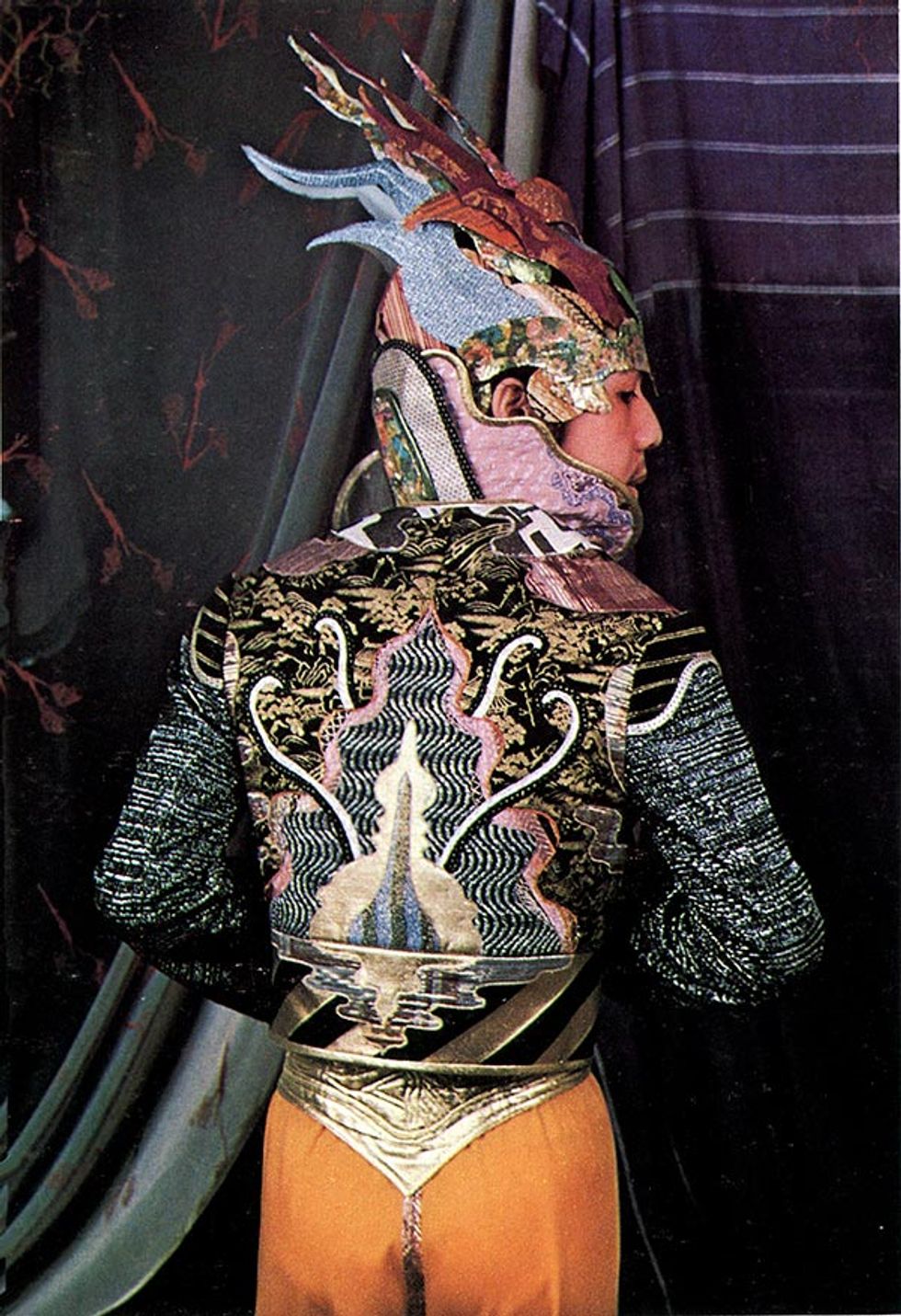

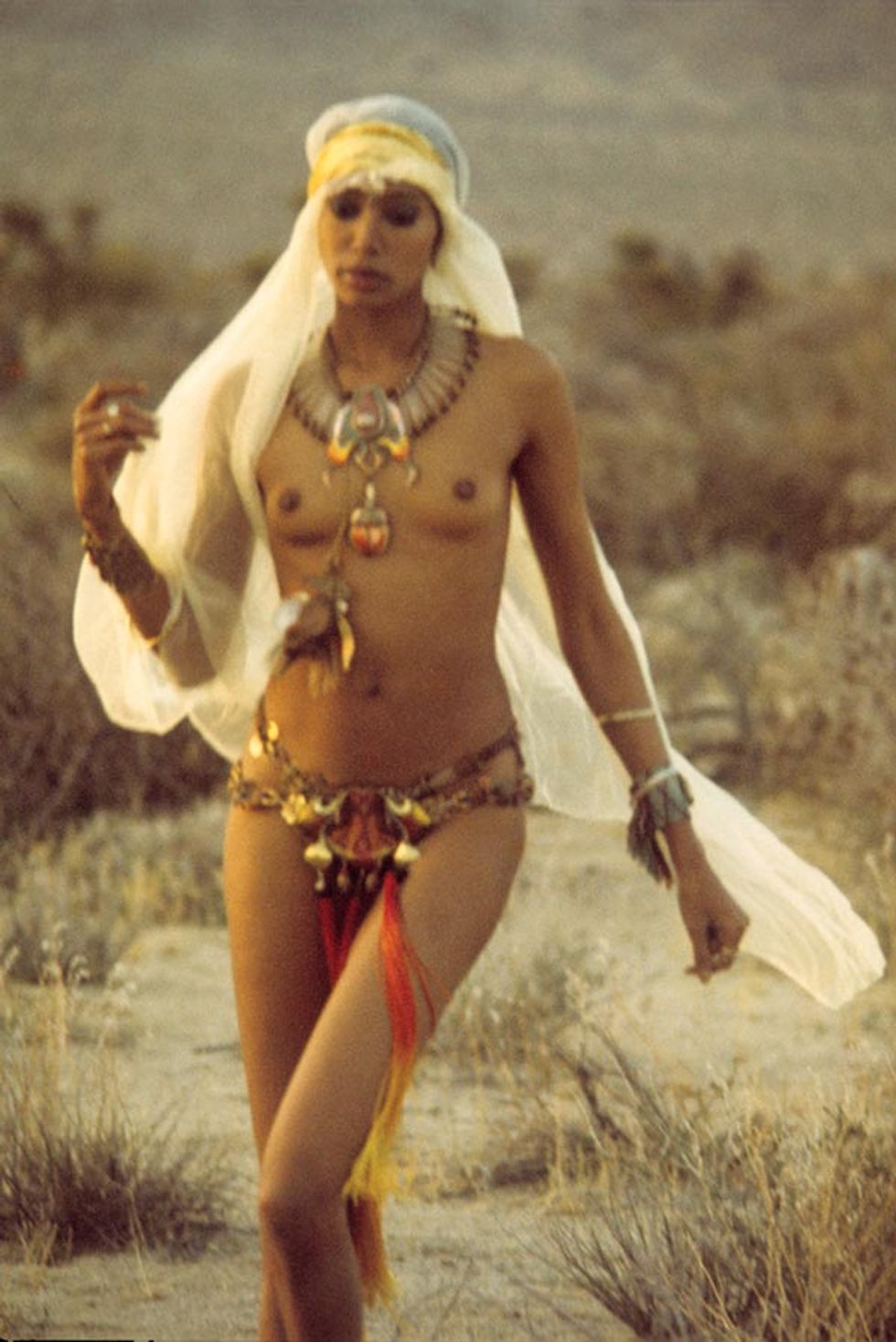

Unlike Hart and McGowan, Fayette Hauser, an original member of the legendary SF drag theater troupe the Cockettes, struck harmony at high decibels. Admittedly operating under the influence of a wide variety of hallucinogens from 1968 to 1972, the Los Angeles native exorcised her childhood demons by making ostentatious costumes out of resale shop treasures, including vintage striped jackets, Gypsy-style belled sashes, colorful wigs, and feather boas. (Though much effort went into building each elaborate ensemble, the ultimate liberation came from the eventual shedding of the garb onstage during the ensemble’s riotous shows, which bore such tawdry titles as Journey to the Center of Uranus and Tinsel Tarts in a Hot Coma.) Writer Horacio Silva, in a New York Times article about the late Cockettes frontman, George Harris (aka Hibiscus), described the group’s sartorial stamp as “equal parts cosmic gypsy and rock groupie…chic freak.” Funk and flash at its sauciest.

“Chaos is a great metaphor for funk and flash,” says Melissa Leventon, a fashion history professor at the California College of the Arts. “The artisans had an uncanny ability to layer very different sizes, colors, ideas, images, and textures to create confusion that actually made sense.”

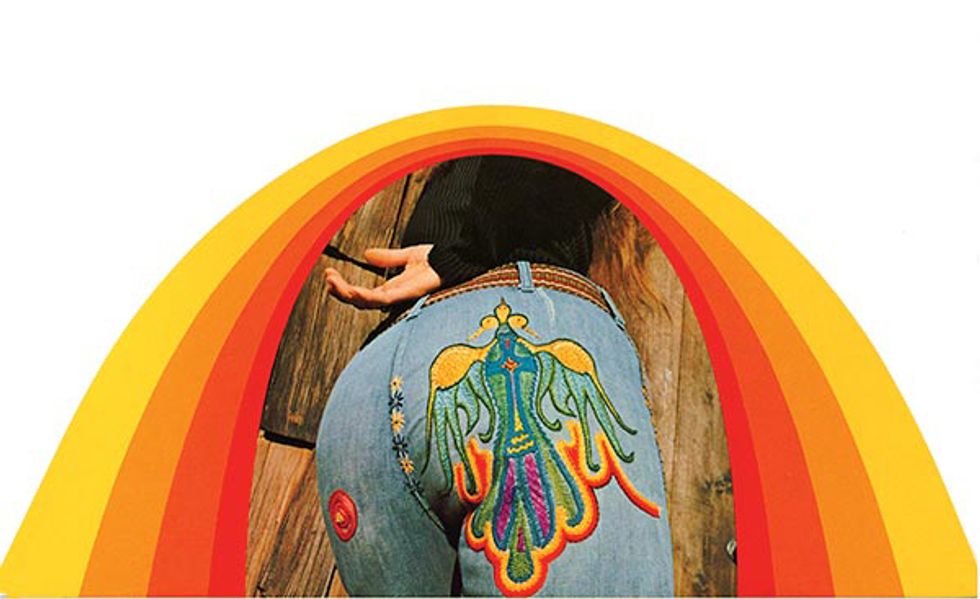

As such, within the funk and flash orbit, scorpion claws, raw diamonds, and ghost crystals can harmoniously coexist, as they do in Alex & Lee’s heritage OM 887 choker. Erotic emissions can strikingly merge with cartoonish blooms, as they did when Alexandra Hart embroidered what she calls “an exploding cock”—a decidedly floral vision she claims appeared to her during an orgasm—onto the hem of a denim skirt. (This metaphorical handiwork is featured on page 19 in the 2013 reprint of Native Funk & Flash.) And a Boy Scout uniform—that innocent emblem of American virtue—can be repurposed into a beatnik pair of knockaround boots, as the Apple Cobbler accomplished with one set of regimentals. McGowan swears his motives weren’t intended to be un-American.

“Don’t read too much political intent into hippie style,” says Leventon. Although there have been examples of politically charged fashion through the ages—during the French Revolution, for instance, young anti-gov aristocrats donned blood-colored ribbons around their necks in solidarity with the thousands who were guillotined; the punk era generated shredded and safety-pinned anarchist designs—funk and flash probably isn’t going to go down in history as one of them.

Despite this, the Oakland Museum of California’s new “Radical Acts” exhibit, which opened in July, features heirlooms from the book—Hart’s embroidered phoenix jeans, Alex & Lee’s Tin Can Marilyn necklace (pyrite, smashed tin, and eyes dissected from a print of Andy Warhol’s iconic Marilyn)—alongside photos of the Black Panthers and women’s lib pioneers. “Funk and flash artists may not have been activists, but they were still searching for alternatives,” says OMCA associate curator Christina Linden.

In high fashion, the era’s “rich hippie” look was defined by designers Halston, whose tie-dye caftans draped starlets Ali MacGraw and Marisa Berenson, and Thea Porter, whose vibrant ethnic designs were worn by Elizabeth Taylor and socialite–cum–gypset muse Talitha Getty. The boho-luxe designs were hailed as “peacockerie.”

Fast forward to the 21st century: In 2002, a hullaballoo erupted over a patchwork vest designed by Nicolas Ghesquière for Balenciaga—a blatant copy, he admits, of a 1973 Mayan-inspired work by Kaisik Wong, the late SF artist and close friend of Salvador Dalí. Ghesquière coveted the piece while eyeing a tear sheet from Native Funk & Flash, testifying to the niche style’s cultish reach and, at least for this major-league designer, inescapable grip.

John Galliano and Marc Jacobs both credited the Cockettes for inspiring their Spring 2004 collections. While decidedly more romantic than “hippie acid freak drag” (as Paris–London subculture blog The Other describes the troupe), Jacobs’ models sashayed the runway in resale shop–inspired faded floral dresses and petticoat-fortified velvet prairie skirts. Meanwhile, at Dior,

Galliano tapped into the Cockettes’ theatrics, merging what Style.com dubbed “Victorian dolls and Brooke Shields in Pretty Baby…overblown transparent sleeves, eyelet tutus, marabou-trimmed rosebud-print corsetry, fluttery panties, white knee socks.”

While Leventon claims that “funk and flash is not a style that is ‘in’ at the moment,” Simon Ungless, director of fashion at the Academy of Art University, says otherwise. “I see a lot of the funk and flash influence in the work of today’s young designers,” admitting that modern Northern California artists may be especially predisposed to the contemporary folk style. He praises Academy of Art alum Jaci Hodges for her couture interpretation of funk and flash in her Fall 2014 graduation collection (think patchwork garments of bold color and big prints), and acknowledges the steady ascent of “slow fashion”—the sartorial equivalent of the Slow Food movement—at the hands of deft hobbyist designers.

“Even if the work can be pedestrian, it is valued for being truly expressive,” says San Rafael–based Liza Yee, whose handcrafted necklaces and headpieces channel “nature sprites and ancient craft” and manifest from a classic funk and flash tool kit: camel wool, leather, crystals, and bells.

Other members of this tribe include Jess Feury in Berkeley, whose patchwork and handwoven pieces, flashed up with sequins and 1920s metallic thread, “don’t feel right until they are disassembled and then reassembled into something new”; and Nevada City’s Tehya Shea, self-proclaimed “feral Yuba maid” (your guess is as good as ours), who describes her driftwood-spiked wall tapestries as “woven medicine talismans of magic and power.”

If there was ever any doubt about funk and flash’s historical relevance or longevity, the heartfelt designs and potent imaginations of the next generation should elicit healthy optimism. Alexandra Hart offers a more scientific breakdown for the continuing evolution. “I suspect the Theta brain wave is responsible, since it generates creativity,” she says. “It’s my favorite brain wave.”

In a funk? Enter to win funk and flash creations from the next generation of countercouturiers in our Instagram contest. Post your best Summer of Love-inspired outfits with #7x7Funk for a chance to win one of three boho-chic pieces from emerging Northern California designers.

See “Radical Acts” at the Oakland Museum of California

This article was published in 7x7's September 2014 issue. Click here to subscribe.