Mild to moderate panic ensued when San Francisco glass sculptor Nikolas Weinstein realized that the borosilicate tubes he required for a mammoth-scale installation of thick, hydra-like tentacles—a whole ocean of them—weren’t going to make it to the Cosmopolitan residential towers in Singapore. Because each 20-foot tube measured just 20 to 80 millimeters thick, shipping hundreds of the fragile chutes from Europe seemed to be a mission damn near impossible.

At such pivotal moments, when those of lesser composition would be inclined to throw in the towel, Weinstein kicks into high gear. “There’s a very fleeting but extremely satisfying moment that transpires when I solve a design dilemma,” says the Noe Valley resident. “These sculptures are a testament to a certain stubbornness. My crew and I spend, at minimum, half our time not getting it right. But we’re always optimistic that we’ll figure it out.”

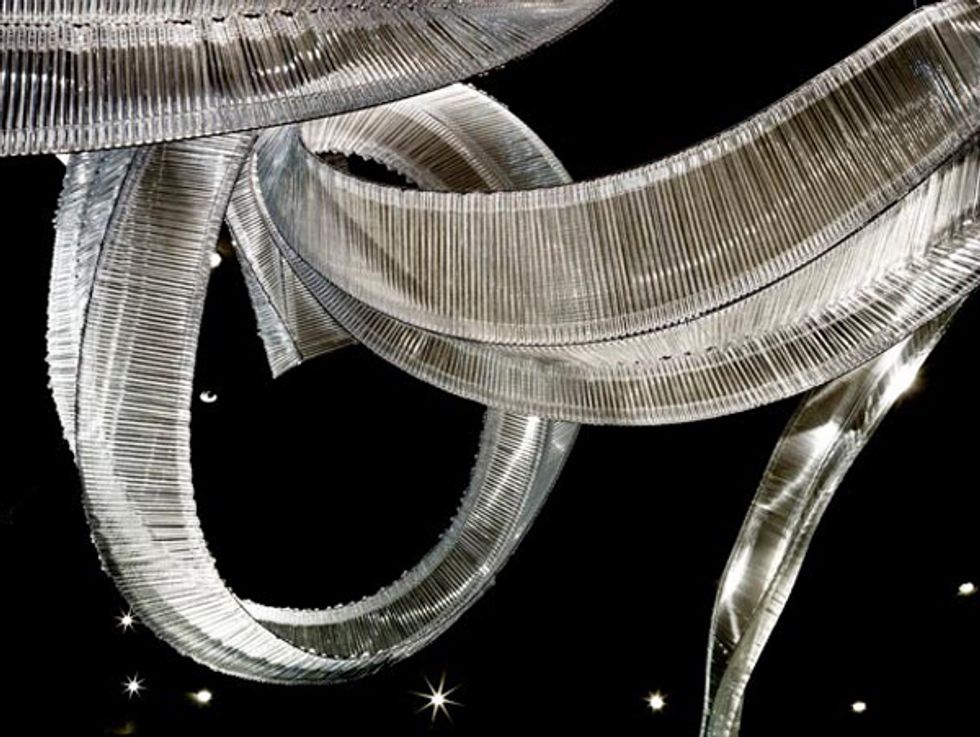

Weinstein credits his ongoing commissions in Asia to the continent’s more adventurous tastes in art. Case in point: this dynamic work, commissioned by the Nan Fung Group, in Hong Kong’s Courtyard by Marriott.

In the end, the tentacles at the Cosmopolitan were made of smaller segments of tubing, fused together to achieve the desired length. Where these joints were made, the light would catch—in the same way diamonds like to ensnare rays—and then bounce off the bonds for maximum sparkle, a fiery bonus that would not have occurred had things run according to plan.

“I always like to make room for serendipity,” says Weinstein, 45, from his studio-warehouse, located on the fringe of the Mission, which he saved from an uncertain destiny as a morgue (but that’s another story). His first commission, the 2001 Pariser Platz 3 Chandelier—a scattering of cloudlike forms that hang in the atrium of the Frank Gehry–designed DZ Bank in Berlin—could also be considered a stroke of luck, because his repertoire until that point comprised mere “sculptural follies” no more than two feet in length. “Glass is so mercurial. It’s dripping, it’s honey-like—you have no choice but to let fate guide you at least part of the way,” he says.

With the appearance of effortlessness, this 2011 sculpture inside Tokyo’s K-Tower belies all the seismic engineering required to bring it to life.

The molten hex that glass cast upon Weinstein more than two decades ago—a far cry from the two-dimensional monotony of stained glass, which was his gateway to this art form while fresh out of college—also happens to be a source of pride. And sometimes, creating such sweeping, supple, serpentine forms, from a material more commonly known as hard and brittle, can backfire. “When I overhear someone say that my work looks like plastic, I cringe,” says Weinstein. “Plastic doesn’t come close to the clarity and sheen of glass.”

From this angle, the 2009 skylight installation for Singapore’s Capella Hotel looks like the hem of a frothy ball gown.

To exploit these virtues, many of Weinstein’s commissions are hung in spaces that are naturally flooded with sunlight. At Bar Agricole in SoMa, for instance, glass “fabric” billows from three large skylights; in a hotel on an island off the coast of Singapore, a jellyfish-like sculpture floats down from the ballroom’s radiant oculus; and a ribbony work meanders, loops, and twists its way through the two bright lobbies of the InterContinental Hotel in Shanghai. (Weinstein envisioned this last piece as a loose line of Chinese calligraphy, but the locals had other notions. “I heard one Shanghai man say, ‘Oh! Dragon!’” says the artist in his best Mandarin accent.)

Weinstein intended this serpentine piece in the lobby of Shanghai’s InterContinental Hotel to conjure a line of Chinese calligraphy.

If you were to construct a heat map of the world indicating the locations of Weinstein’s work, the brightest cluster would be on the continent of Asia. “I have little to no presence in the United States,” says Weinstein. “In a weird way, Asia is a lot more open to new things. There’s not the same dominance of European culture there that you find here.” The latest additions to that global outlook include an elegant, circuitous piece in the Great Room of the JW Marriott in New Delhi and a bundle of torqued chutes in Hong Kong’s Opus Hotel—also a Gehry design—that create a kaleidoscopic spectacle when light passes through them.

Although such prismatic feats are certainly special attractions, it is no longer enough for art to exist simply for the sake of enchantment or beauty. Like any virtuoso, Weinstein constantly searches for ways to deepen his work. Currently, he is unriddling the ways in which his sculptures can function as diffusers of harsh sunlight. “Glass wants to be light,” says Weinstein. “I’m just helping it achieve its dream.”

While light plays a leading role in Weinstein’s designs, he can also masterfully evoke a gentle breeze, as seen here in his piece at Bar Agricole.

Get the full scope of Weinstein's work in our photo gallery!