“I feel like the world is a place I bought a ticket to,” the photographer Garry Winogrand is quoted saying in Garry Winogrand, now at SFMOMA. This unprecedentedly comprehensive exhibition, consisting of hundreds of snapshot photographs taken between the early 1950s and the time of the prolific artist’s early death in 1984, offers viewers a ringside seat to the unique spectacle of American society as it mutated over the course of those incredible decades–an opportunity not to be passed up.

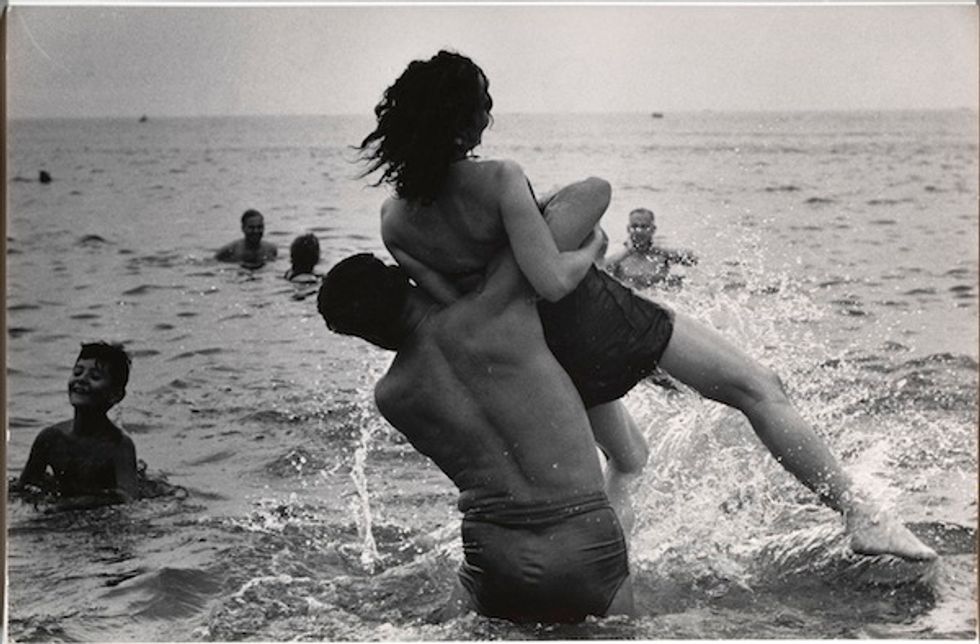

Strolling through this rather gargantuan show, one has to wonder why recognition of Winogrand is so late in coming, compared to peers of his like Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander who likewise aimed their lenses at postwar America. Winogrand’s eye is virtuosic, allowing him to frame the most momentary of events – a man lunging into the ocean with a woman in tow, a couple strolling by with their pet monkeys – in the most striking way possible. It seems like Winogrand was always at the exact right place at the right time.

Perhaps it was Winogrand’s prolifity that made him hard to champion. More interested in shooting than editing, Winogrand produced a staggering amount of images that never left the roll. Indeed, a significant number of works in SFMOMA’s exhibition are developed here for the first time (Leo Rubinfien, a protégé of Winogrand, stepped into a unique curatorial role to select these images, which the artist himself had perhaps never even seen). Or perhaps it is the fact that the bulk of books on the artist tend to divide his work by subject matter (women, politicians and animals were among his favorites), an approach that oversimplifies Winogrand’s practice.

More likely, however, it is the fact that Winogrand’s later work, much of which features the streets of Texas and Los Angeles, did not meet the critical applause that his earlier, New York-based photos did. Passing through the second half of the exhibition, it is no wonder why: By comparison to the roiling, ecstatic absurdity of Winogrand’s Manhattan of the 1950s and 60s, the later works have a dull, dreary quality. The lighting is harsh, the spaces empty. Subjects, like those at the Texas rodeo or on the Venice boardwalk, are pitiably rather than amusingly vulgar. In a word, things got ugly.

Dividing Garry Winogrand into three sections, “Down from the Bronx,” “A Student of America,” and “Boom and Bust,” Mr. Rubinfien presents an argument that it was not Winogrand who grew cynical, but rather post-Nixon America that did. Winogrand simply continued to watch the show, knowing himself to be a peripheral actor in it.

Those looking to enjoy pictures of an age of lost innocence, where the seeds of mendacity and decay are apparent while everyone still looks they’re on Mad Men, will find a robust exhibition in this one’s first two sections alone. Those willing to engage with the larger, more distressing portrait of American life that Winogrand’s work presents must bear up to take in a somewhat exhaustingly massive exhibition consisting of all three parts.

Leaving the exhibition’s bleak third section, which hits its nadir with the image of a woman collapsed on a street as a Porsche sports car zooms past her, one cannot help but wonder what the past thirty years would have looked like through Winogrand’s lens. Who is photographing America now? Someone must do so, for the show goes on.

Garry Winogrand runs through June 2 at SFMOMA (151 Third Street)