Most documentary photographs tell only one version of a story, the perspective captured by an outsider looking in.

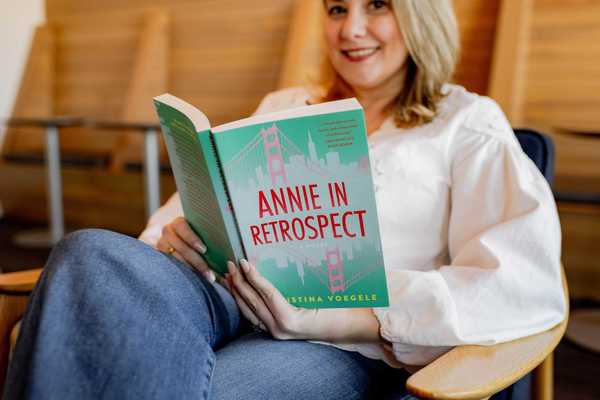

But people aren’t so one-dimensional. Distilling their lives and experiences through the flash of a camera distills their humanity, too. That’s a fact that’s never sat well with Ashima Yadava—not when she was growing up in New Delhi, India, not after she moved to San Francisco to further her education, not when she was a Director’s Fellow in Documentary Photography at the International Center of Photography in New York in 2020.

By the time Yadava began shooting portraits of quarantining families in the front yards of their homes at the start of the pandemic, her awareness of the problem had grown so acute, she could no longer ignore it.

“I had this moment where I said, ‘what if I had these people color [these photographs] or embellish them to share their own perspective,” she recalls. “I wanted to make more than a picture or record of this time; I wanted to know how they were seeing themselves in this moment.”

And so, Yadava did something radical: she democratized the images, handing photographs back to the families in them to adorn as they saw fit. Some added color to the black-and-white pictures, others corrected mistakes or added elements that were not actually there. In one portrait, a basketball player corrected the record by drawing a ball in their own hands after the camera’s flash captured the real one in the hands of their sibling.

It was a perfect metaphor for the project, says Yadava. “All of these stories are also enriched because they directly included the voices of the people that were in them.”

Currently on exhibit at Chung 24 Gallery, Yadava’s Front Yard series doesn’t just illuminate the experiences of families across socio-economic classes and ethnic backgrounds in those early days of Covid uncertainty; it illustrates the nuances and dichotomies of those experiences in a way a camera alone could never capture.

Yadava has known since a young age that dualities can coexist. In New Delhi, “beauty and ugly live together,” she says. “It’s such a land of contradictions.” Here, in the Bay Area, to which she immigrated two decades ago, although distinctions between communities and individuals are less visible, they are no less relevant.

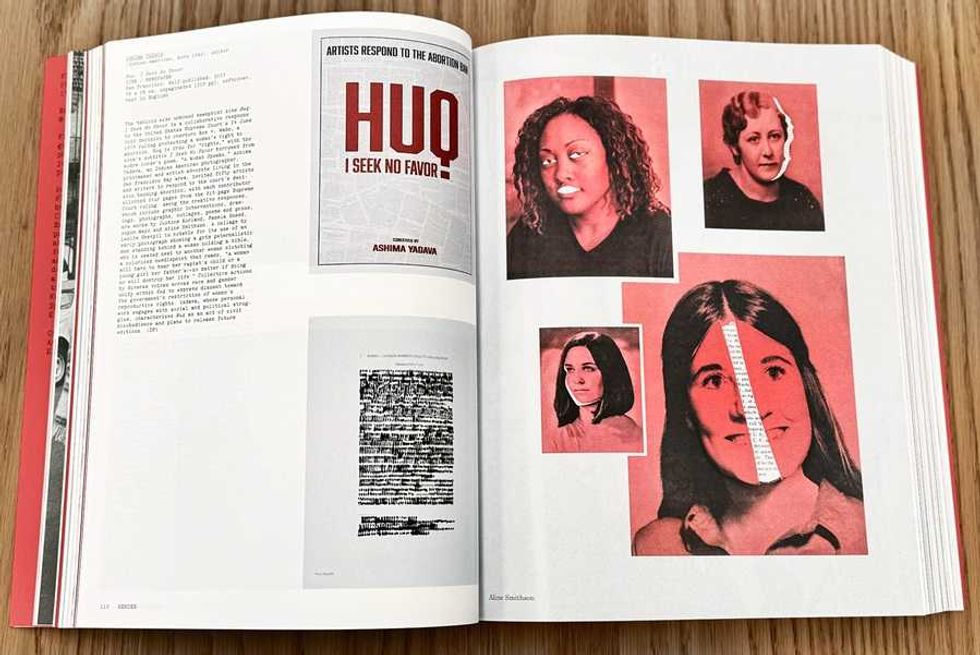

For Yadava, art is a way of drawing them out, of engaging communities without the preciousness or intimidation associated with galleries and museums. And while photography is often her medium of choice, the camera’s lens is just one of many tools she uses to illustrate humanity’s messy, braided, polylithic reality. Yadava’s ongoing project Huq, I Seek No Favor, a printed ‘zine similar to those that interpreted counterculture visually and in words in the ‘90s, is another.

Instigated by the overturning of Roe v. Wade, Huq was a way for Yadava to reckon with the court’s draconian decision. “I needed to do something about that rage and helplessness I was feeling at the time,” she explains. “I reached out to a bunch of people [and found that] we shared that common sense of despair about what we were feeling.” On the printed pages of the docket, Yadava unleashed her anger, tearing them apart, making haikus from them, marking words within them—and found herself “weirdly empowered.”

And so, she turned her solitary action into collaborative dissent. “I reached out to 50 people, gave them each four pages of the docket, and said please respond to these four pages however you like,” she explains. After the respondents drew and colored and wrote on the pages they were given, Yadava collected them back together and printed a ‘zine filled with their voices.

That first publication was just the start of an ongoing project; “this way of working collectively, building these little bridges and channels, activating these places in the community, has sort of become a way of life for me,” says Yadava.

With Huq ‘zine workshops in colleges and universities, she is reinvigorating a form of indie artistry in which both beauty and ugly naturally exist side-by-side. Yadava is also the chair of programming and sits on the board of directors at SF Camerawork (Fort Mason Center, 2 Marina Blvd., Bldg. A, Marina), where she's working to engage the local community and establish an incubator space for Bay Area artists.

“We’re conditioned and led into thinking that we should do something in a certain way but there are seven billion people on this planet, which means there are seven billion stories and seven billion ways to do something,” says Yadava. Bringing them together, connecting people and ideas through collaboration, is the intersection from which art draws its power.

// Hear more about ‘Front Yard' at Ashima Yadava’s artist talk at Chung 24 Gallery on January 31st at 3pm. ‘Front Yard’ is on display at Chung 24 Gallery through February 14th, 698 Pennsylvania Ave. (Potrero Hill), chung24gallery.com. Learn more about ‘Huq: I Seek No Favor’ at huq-iseeknofavor.com.