At 8:37 a.m. on April 19, BobCr published his first opinion of the day on SFGate, San Francisco Chronicle's online home, a response to an article about a U.S. Supreme Court ruling on Chipotle Mexican Grill's access for the disabled: “For the Liberals, Useful Idiot parking spaces would be needed since they can barely find their way out of their house." At 8:53 a.m., he moved on to an article about the S&P downgrading its outlook on government debt and posted six comments including this one: “Why do Useful Idiots have no idea what is Socialism. ... that is why they are called Useful Idiots."

By 9:07 a.m., BobCr was commenting on a story about a bill that would require presidential candidates to prove their U.S. citizenship: “Why do Chimps and Obama both have no Birth Certificate? However, One can only speculate which village in Kenya is looking for its Idiot." After 16 posts on that topic, he circled back to the Chipotle case before returning to the issue of the president's birth certificate. By 8:59 p.m., BobCr had posted to SFGate a total of 50 comments, some of them paragraphs long, before starting up again the next morning.

You could dismiss BobCr's behavior as obsessive, but he's not alone. Scrolling down the comments on any given SFGate article is often like rappelling into a chasm of personal bias and circular chatter—enough to make you question humanity. At last count, SFGate's comments—many of which run for pages longer than the original stories—receive almost 4 million page views a month according to an SF Chronicle article published two years ago. (When contacted, SFGate refused to share their current traffic numbers.)

Over on SFist's city blog, the topics are lighter and often composed of ironic commentary on local news, politics, and culture. But its readers are just as talky. MrEricSir has 502 comments and regularly argues with fellow reader Miles_Long about everything from sex workers to the San Francisco Entertainment Commission.

On our own magazine's website, 7x7.com, the articles that have garnered the most comments in the past six months have involved such significant issues as the city's cutest dog, best burritos, and Blue Bottle Coffee's failed Dolores Park kiosk. “One of the most ugliest dogs I've ever seen," wrote commenter Tobau of Toaster, the perfectly innocent pup who won our online pet poll. In response to local activist Chicken John Rinaldi's (no relation to the author) stance against Blue Bottle and his long-term relationship with Ritual Roasters owner Eileen Hassi, a reader who tagged himself Boycott Ritual admonished others to “spit on [Ritual's] stupid vegan donuts" and pointed out that “Chicken John can't answer questions honestly, he just acts like a little bratty bitch." To which Anonymous chimed in, “Most all of you are low life, P.C. whores that are ruining San Francisco."

Ah, the joys of free speech.

Five or six years ago, things were different. Readers could post their opinions to discussion boards and newsgroups but typically not on large news sites such as SFGate or The Huffington Post. When online commenting appeared around 2005, the media's traditional one-way communication suddenly became a two-way street, with opinions and clicks flying like dirt on a playground.

It's a chicken-and-egg equation, however. “Commenting is the secret sauce of social media," says BJ Fogg, a social psychologist who studies online behavior and heads up the Persuasive Technology Lab at Stanford University. “Blogging wouldn't have taken off had comments not been allowed. When you get a comment, even if it's not positive, it's a reward. It's attention and acknowledgment. It's reinforcing."

Not for Mark Morford, SFGate's controversial and highly read columnist. “I never read comments," says Morford. “I used to and then realized that within a dozen comments, it devolves into a horrible off-topic mudslinging diatribe. I'd never learn anything or get any real feedback about the column at large or the topic at hand, so now I ignore them entirely."

This is in stark contrast to how Morford treated feedback in the days when readers emailed him directly. Back then, within hours of posting a column online, Morford would receive several hundred emails: criticisms, praise, corrections. “It was an instant feedback loop," he says. “I read them all, replied to a few, had discussions, got to know my long-time readers. That's vanished entirely. Now I get three or four emails per column. They'd rather get 'published' anonymously on SFGate."

To Morford, the difference in the quality of feedback boils down to one thing: anonymity. “I think anonymous commenting has single-handedly destroyed most discourse on the Internet," he concludes. The widely circulated “Greater Internet Dickwad Theory" cartoon by Mike Krahulik puts it this way: Normal person plus anonymity plus audience equals total dickwad.

Psychological research bears this out, says Fogg. “It's not just with commenting, and it's not just online. It's in all situations. Most studies show when people are anonymous, they behave much worse."

Think of the other common situation in which we interact with masses of strangers who don't know our names or where we live: driving. From the safety of our cars, it's easy to see the world as a stage on which we are the central player. Others' mistakes—a too-slow turn, a too-fast merge—can invoke an illogical rage, expressed in the form of laying on the horn or yelling, that we'd never express face-to-face.

Most online commenting is even more anonymous. Using Yahoo, Gmail, and the like, users can create endless nicknames or “sock puppets" that conceal every signal humans have to identify and interact with each other: face, name, gender, age, location. Cut loose from their real-world identities, trolls are free to tell the world what they really think—or at least what some deep-down part of them thinks.

Some argue that although anonymity tends to breed more personal invective, it also provides protection for opinions that Joe Schmoe might not want his employer, wife, or mom to know he holds, creating a truly uncensored public medium that simply didn't exist before the Internet. Of course, political and corporate whistle-blowers have traditionally retained the right to anonymous expression in the media for decades. But short of ensuring job or personal security, everyday online anonymity begs the question: Can a person claim his civil rights without first claiming his identity?

Heather Champ, who worked as director of community at photo-sharing site Flickr for five years and now runs Fertile Medium, a consultancy she cofounded to help sites design and lead their communities, has a perspective on free speech that comes from being born Canadian. “I'm not sure Americans realize how their concept of freedom of speech colors their understanding and makes them feel entitled to that freedom everywhere," she says. “But we have to remember that these sites are businesses and not countries. At a certain point, if you're letting it all hang out, you're likely going to hit a fence that somebody's put up."

These fences take various forms, starting with a site's terms of service, which usually state the obvious: no profanity, obscenity, or language that is abusive, sexually explicit, derogatory toward gender, race, ethnicity, national origin, religion, sexual preference, or disability. Ideally, a community manager monitors the comments and takes down those that violate the terms. Look through SFGate, for instance, and you'll see frequent instances of comments removed for being abusive or otherwise violating the terms and conditions. Some users have been blocked by staff altogether. Comments on SFGate are also ranked in popularity based on the number of “likes" and “dislikes" and can be posted or recommended to a dozen other sites.

Online newspaper The Huffington Post goes a few steps further to categorize its comments and commentators, letting them earn badges that denote them as networkers (users with lots of friends and followers), superusers (people with lots of comments and shares), or moderators (those who have correctly flagged at least 20 comments for deletion). In essence, The Huffington Post is slowly converting its community into a self-moderating forum: Moderators who consistently perform by flagging at least 100 comments can eventually delete comments on their own.

This, says Champ, is where the online comments are headed. “Systems where people can vote up or down on comments allow the conversations to collapse, to eliminate the noise," she says. “Everyone can speak, but it's the thoughtful back-and-forth that bubbles up to the top." This could be one reason why users hail The Huffington Post as an example of an intelligent online forum. Internet expert Fogg says, “On HuffPo, it feels like it's the smartest people who are commenting."

But the online newspaper's more-is-better rating system isn't the only way to go. Slashdot—the wildly popular technology news site that coined the default name “Anonymous Coward" for unidentified posters—created a comprehensive moderation algorithm in an effort to sort the wheat from the chaff. Every 30 minutes, the system doles out moderation tokens to users from the middle of the pack—those who are neither overly engaged (read: obsessed) nor lurking. These reader-moderators then rate comments with points ranging from negative one to five and descriptors such as off-topic, redundant, insightful, funny, and informative. “That way, you don't end up with a static list of unpaid moderators but with a flowing snapshot of the community," says Champ.

Each reader can also set their own threshold to edit comments from their screen. Set it to negative one and you'll see them all, but raise it to five and you'll see only the best. (Lest you wonder why a site that bills itself News for Nerds would need such an elegant matrix, note that a recent Slashdot post about the metric versus imperial measurement systems elicited 2,279 comments.)

There are other examples of sites that host fervent but civil discussions, the kind that actually help contextualize an issue instead of drowning it out: SF-based web magazine Salon, where reader comments are formatted to resemble letters to the editor, and The Well (owned by Salon Media), the iconic Bay Area discussion site founded by Whole Earth Review editors Stewart Brand and Larry Brilliant, where some of the smartest people on the planet debate the issues using their real names.

And of course, there's the The New York Times' site nytimes.com, where the moderation is old-school. Many of the articles can't be commented upon at all, and where comments are allowed, they are screened by a team of eight moderators before posting. On the Help section of its site, The New York Times explains its policy thusly: “By screening submissions, we have created a space where readers can exchange intelligent and informed commentary that enhances the quality of our news and information." They also have more stringent standards for what won't be tolerated, including not just the usual personal attacks, vulgarity, profanity, and commercial promotion, but also “impersonations, incoherence, and SHOUTING." Watch your p's and q's and capital letters.

Back here in the Bay Area, geek news site TechCrunch has eliminated all that nastiness in one fell swoop. Since it started requiring its users to log on via Facebook in March, TechCrunch's comments—which have dwindled considerably—are no longer what Champ characterizes as “bat-shit crazy" or what TechCrunch writer MG Siegler has called “a cesspool of bullshit." Now they're more civil, accompanied by the friendly faces, real names (in familiar blue text), and web of relationships that come with Facebook.

The blogosphere has taken note of Tech-Crunch's move, which it frames as an experiment. In March, online magazine Slate published an article titled “Troll, Reveal Thyself," in which writer Farhad Manjoo made the case for disallowing anonymity. Others have criticized TechCrunch, though, citing concerns about privacy, distrust of Facebook, and a preference for logging in via Twitter, where identities are more specific than on Facebook.

It brings up a few salient, 21st-century questions. Like, where does your “real" personality live online? Is there such a thing? And what exactly is anonymity?

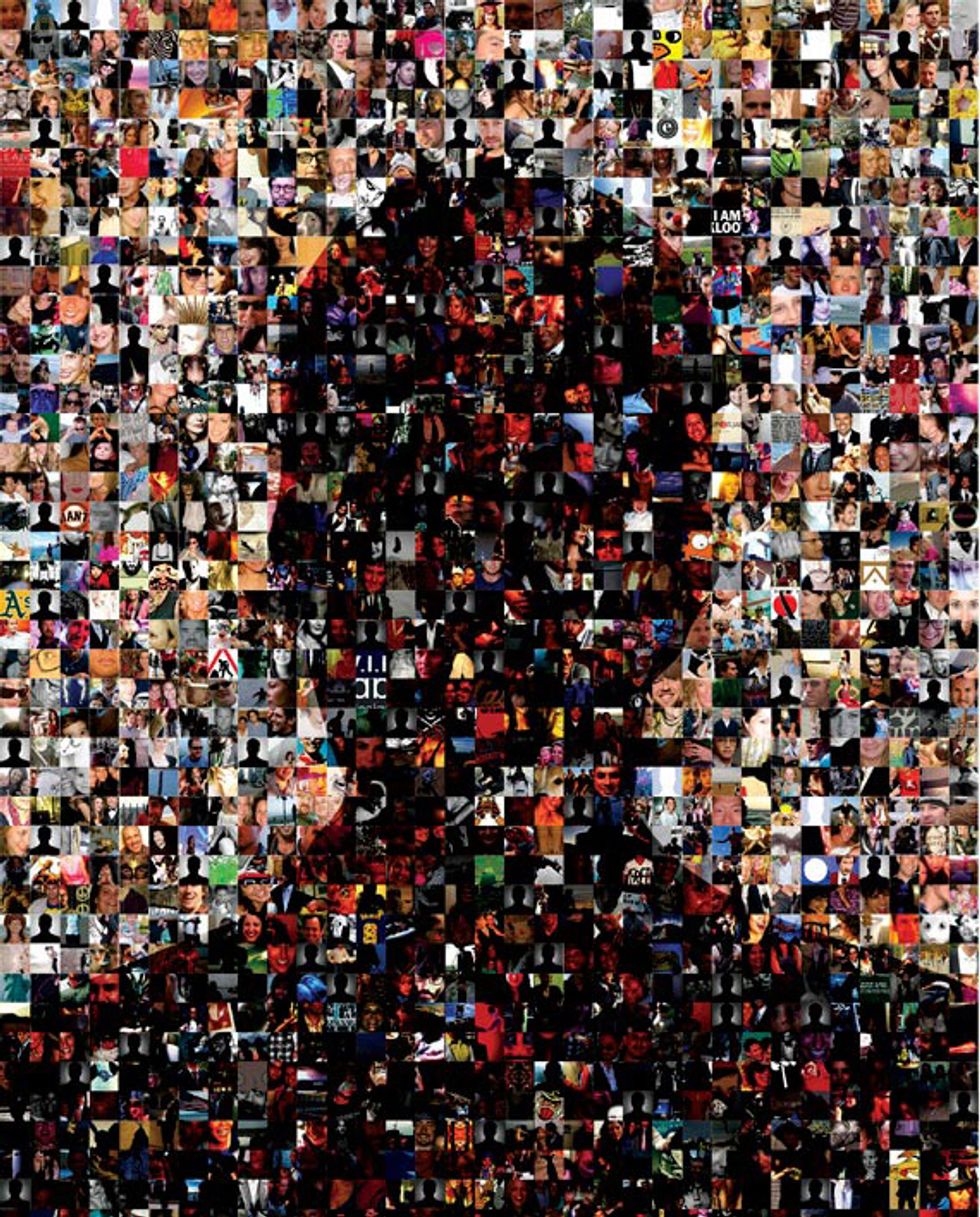

Champ has problems with relying only on Facebook for a person's identity: “Who I am on Flickr versus on Tumblr versus on Twitter are all slightly divergent aspects of my personality." It's also apparent that identity occurs in gradations, starting with the anonymous and moving on to monikers with no avatar, ones with an avatar, real names, and real names with photos. For instance, when users enter a moniker but not an avatar, their default icon often appears as a generic semi-smiley face. “When readers see that icon," says Champ, “they know you haven't taken the time to change it to something personal. They think, 'Why should I take your opinion seriously when you're obviously not as invested as I am?'"

But even made-up names alone provide some semblance of identity. You may not be privy to BobCr's real name, but if you read his comments, you might begin to feel like you know him regardless.

SFist editor Brock Keeling decided to disallow anonymous comments in 2007 because “it provided the possibility to be a major asshole," he says. But he sees real names and monikers in the same, non-anonymous light. “It's nice when people use either their real name or a made-up identity consistently to create a voice. It forces them to stand by their words."

“It may not be your true identity," says Fogg, “but if users feel that Riverfrog3 is an ongoing identity, then it's not anonymous anymore. Identity has more to do with perceived audience."

Though it's hard to argue against the fact that everyone constantly edits their real-life communications to their audience, Morford's not interested in splitting hairs. “Strong avatars with personalities can still falsely represent how a person would present themselves in person if I met them for a drink," he says. It's charmingly old-fashioned, this propensity to want people to be the same person they were yesterday, with a name you can remember, a face you can recognize, and a set of opinions you have heard in a bar or around a dinner table.

To keep commenters behaving, avatar or no, Fogg suggests that a blogger's job should be like that of a dinner-party host. “There are ways to craft and guide the conversation," he says. “Involve the author, get the comments going in an interesting direction. Email your friends, and ask them to post."

On SFist, Keeling and other writers take this approach, regularly jumping into the fray. “It usually livens things up," he says. “More importantly, it helps move the conversation along." Unless, he adds, “your commenters are of the heinous YouTube variety, in which case you should stay as far away as possible."

Morford laughs aloud at the concept of engaging his commenters. “That's hysterical and very sweet, and if I had 1,000 hours in a day, I'd love to do that," he says, “but it's bullshit." (Ironically, from-the-hip calls of “bullshit" and “asshole," which are so refreshingly candid in person, might get Morford or Keeling banned if posted online.) “If SFGate had more resources, we'd have a staff of moderators round the clock. But I don't even have an editor anymore. We don't have water coolers. The Chronicle runs on three sports writers and an intern. I pray SFGate will go to Facebook comments, but if you take that route, you are guaranteed to slash traffic a hundred times over."

Ay, there's the rub. As do most things, it comes down to money. Though technocrats insist the cost-per-impression model will soon go the way of the dinosaur, those thousands of views are still the most basic way to measure a site's worth—and an advertiser's reach. It's easier to let everyone and their brother comment—anonymously if necessary—because, after all, comments equal engagement, and engagement is a big selling point. Here at 7x7, we're as guilty as the next guy. We don't even go as far as SFGate or SFist to make commenters log in, simply because it dissuades readers from posting.

As far as paying for a staff of moderators? The New York Times might have the money for it, and, having just been acquired by AOL in February, The Huffington Post is likely to have a bit of cash to throw at moderation as well. But Salon has been in financial straits throughout its history. The fact is, most websites, whether functioning as standalones or the online arms of struggling print brands, run on a shoestring. The result is cacophony.

“Five years ago when commenting started, maybe people just wanted to be heard," says Morford. “But now the level of discourse is so low. I think that romantic idea of democracy in action has been buried and lost in this noise and chaos."

Given the lack of capital and staff to throw at the problem, the likely solution may be technological, involving the kind of mass moderation pioneered by Slashdot: an intricate system in which community members edit each other—just like in real life. It won't be perfect, but in the end, it may be the best we've got precisely because of the way it averages things out. As Slashdot founder Rob Malda says: “Some humans are selfish and destructive. Others work hard and fair. It's my opinion that the sum of all their efforts is pretty damn good."

Let's hope he's right.