One hundred years after the birth of jazz, the music—and all it means to the melting pot of America—finally gets an entire building of its own in San Francisco. Say amen, somebody! It ain’t necessarily church, but that’s because this choir swings hard with religious freedom. Jews, Christians, Muslims, atheists, anybody who can keep time is invited to sit in. Please turn in your songbook to the story of Satchmo, of “Strange Fruit,” of “Mississippi Goddam,” and “A Love Supreme.” Let us sing together and become greater than the sum of our humble parts. Now we can finally explore jazz in a house built specifically to present and preserve the art form, as well as educate and inspire our diverse populace about the benefits of blue notes and our nation’s rocky experiment of assimilation. The new SFJazz Center creates a new kind of cultural center where jazz is the central voice in the dialogue. To quote Miles Davis, “So what?”

Well, imagine America without a modern art museum. Imagine if paintings only had galleries to hang in and there were no museums or nonprofits to ensure public access. What if the free market were the deciding factor in what and whose work was shown? Would the greatest painters and paintings be displayed? Would there be room for experimentation and growth? Would that be the best way to experience the art, to ensure its vibrancy and impact?

Of course, people would still paint. Just as jazz musicians have kept their craft alive by playing in compromised settings. For the past 30 years, SFJazz (the largest presenter of jazz on the West Coast) has had to resort to lecture halls, movie theaters, churches, clubs, Davies Symphony Hall, and the War Memorial Opera House—none of which was designed to showcase jazz music. Straight, no chaser, there are more than 125 opera houses in North America. There are easily as many symphonies, most of which have a permanent home. SFMOMA is expanding thanks to a $555 million addition, and Sonoma State just added a classical music venue to its campus for $130 million. So why is it that SFJazz is still scratching for $63 million (which includes a $10 million endowment) to build the first-ever, standalone structure in the country dedicated to jazz? Consider it saxophonist Miguel Zenón versus another Tom Stoppard revival, the SFJazz Collective versus Michael Tilson Thomas, Jason Moran’s Fats Waller Dance Party versus a new opera of Moby Dick. And unlike a Jackson Pollock painting appreciating in your collection, you can’t leverage the Thelonious Monk recording that inspired it.

Rendering of the new SFJazz Center. Photo courtesy of SF Examiner.

There is a whole canon of music—of which I’m a great fan and supporter—created and performed by the white middle class for the consumption of the white middle and upper classes. And it brings up the question of whose stories get told, by whom, and where? Who lays the framework for the argument? In my five years on the board of the SF Opera, I noticed that even when the opera explored a subject like a dead man walking, the main character was white, despite the fact that 42 percent of prisoners on death row are black. I don’t think I’ve seen an opera composed by an African American or Latino. My pal Amy Tan snuck in a libretto once. Score one for a radical Chinese California native (who also likes jazz). Just saying.

Jazz is America’s music. Democratic and inclusive, able to create beauty from our darkest hours, bolstering spirits and giving reason to dance during the Great Depression, serving as our nation’s popular music during World War II, and becoming the drum beat of civil rights. In 1964, Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, “Much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music.” Some argue it is our only native-born art form. Some say it’s our greatest export.

But it was born out of wedlock somewhere in Congo Square—African slave rhythms trading musical twelves with John Souza marches. Someone slipped Tab A into Slot B flat, probably because it felt good, sounded mo’ better. A true color-blind coupling or an immaculate conception? But like any love child birthed by unlikely parents who neglected their offspring, it had to improvise to survive. Immediately.

It lived on street corners and in clubs, drank heavily and did drugs, staggered and sang sadly, matured amid the overlooked and underprivileged, gained confidence, and got to know its neighbors. Then it played fast and loud and demanded solos and virtuosity, persevered despite itself (maybe because of itself?), and defiantly created a sense of self, caught a bus, migrated north and east, multiplied, followed black folks and shadowed whites, went to Japan and France and South America, toured Europe, mirrored our humanity, and showed up hungry on weekends when workers got paid. Like many explorers and eccentrics, pioneers and crackpots, innovators bent on following their own drumbeat, jazz came west too. It arrived in San Francisco to set up shop, getting serious sometime after Bloody Thursday (the 1934 waterfront labor strike), when Harry Bridges had the dockworkers become the first union to integrate, however grudgingly.

Race music? Race card? Unifying music? Union card? Because of blue-collar jobs on the docks and a shift from banking to industry during World War II, there was a massive migration of African Americans to San Francisco, a 600 percent population increase between 1940 and 1945 to 32,001 residents. By 1950, 43,460 African Americans lived in Fogtown. The Fillmore district became known as the “Harlem of the West.” Jazz clubs boomed for obvious reasons. In 1970, African Americans made up 13.4 percent of San Franciscans. But then we lost our industry, moved shipping across the bay, and became a tourist town. By 2005, African Americans made up only 6.5 percent of our population, the steepest decline of any major U.S. city. And we have been rapidly losing our history ever since.

In a way, the SFJazz Center is a rally cry against gentrification and for a new dialogue based on an old message of racial and economic inclusion. The SFJazz Center’s lineup and roster of resident artistic directors (Bill Frisell, Regina Carter, Jason Moran, Miguel Zenón, and John Santos—three MacArthur Fellows among them) reads like a San Francisco census: young, old, multi-ethnic, smart, streetwise. It indicates the direction of our city and its core principles. We will soon see a jazz renaissance (mark my words!), a recovery and reclaiming of our nation’s songs and full history. And because of San Francisco’s progressive spirit and know-how, the precedent of our landmark SFJazz Center happened here first, on the corner of Franklin and Fell streets, in front of Raise Up Off Me Alley, named after the title of jazz pianist Hampton Hawes’ radical autobiography. Not New Orleans or St. Louis, Chicago or Kansas City. Not even New York, with its Jazz at Lincoln Center buried inside a monstrous 2.8 million-square-foot, mixed-use property. We have finally been able to erect a hall to pay homage to jazz. This can only help us move forward in the 21st century. What will come of jazz being the dominant paradigm of a cultural center? I don’t know, but I can hear it humming.

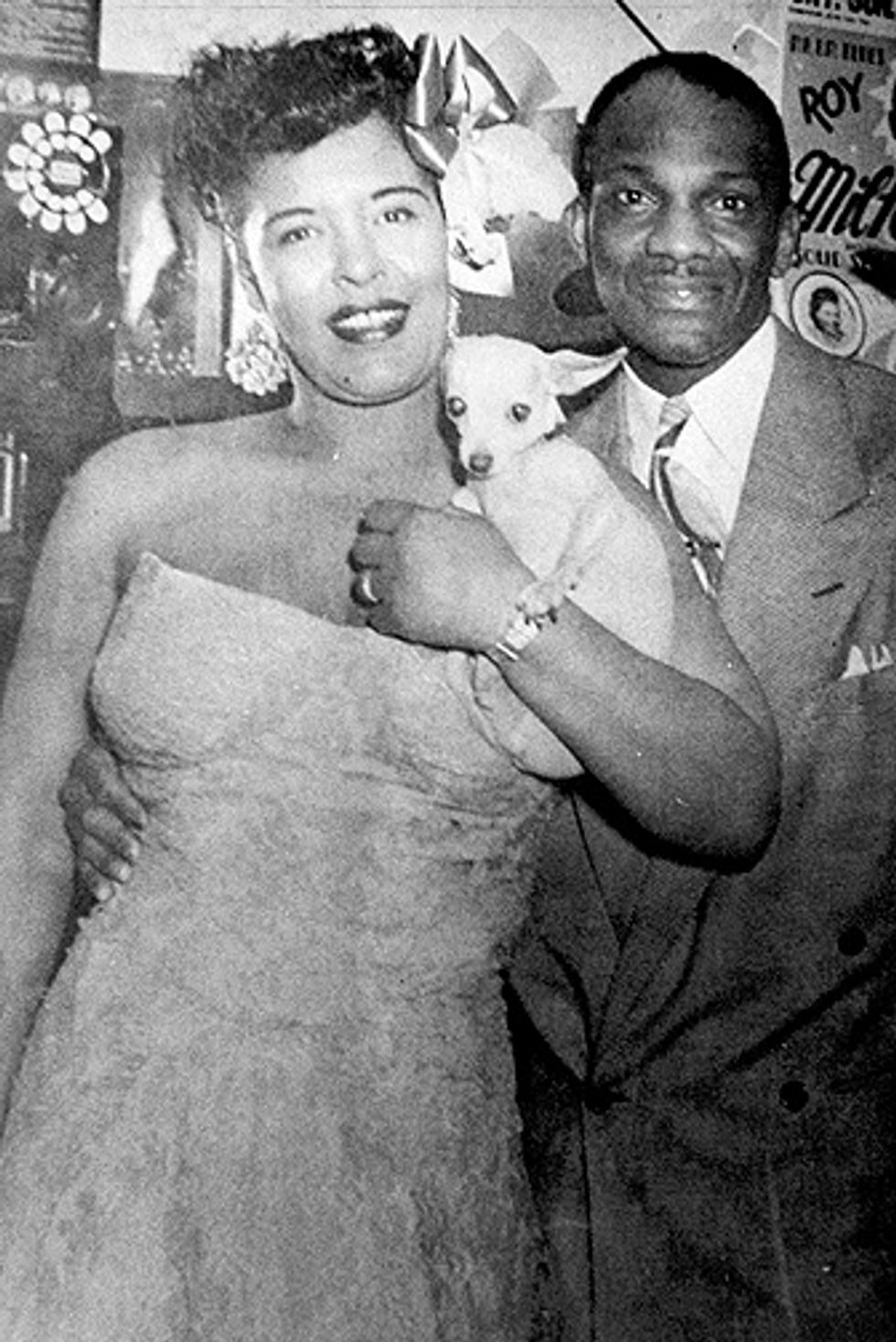

Photo: Billie Holiday and Wesley Johnson Sr. at his Club Flamingo in the mid-1950's. Courtesy of FoundSF.

This article was published in 7x7's December/January issue. Click here to subscribe.