Gentle splashes of fresh water sprinkle over the bow, reviving us as we breeze through islets—more like dollops of jungle spooned from a batter of rainforest than beachy outcroppings. Egrets soar past our path and skid into landing, loons drag their knuckles on the placid waves, and somewhere beneath, bull sharks silently drift along, having adapted to the lack of salt water over thousands of years. My husband and I are on a small skiff traveling through an archipelago of 365 atolls off the coast of Granada, formed from the last reaches of an eruption thought to have happened thousands of years ago, when nearby Mombacho Volcano blew its top near the northwestern tip of Lake Nicaragua.

It’s a scene not dissimilar to one that could have been witnessed by some of our San Franciscan ancestors—Gold Rushers from New York crossed this very lake after landing on Nicaragua’s Caribbean coast and braving a harrowing trip down the San Juan River. On their 46-day journey, their last stop was the port of San Juan Del Sur, now a Pacific coast haven for backpackers and surf seekers that resembles any stretch of beach in Mexico. One of the most popular tourist destinations in Nicaragua, it pales in comparison to the rest of a country drunk with beauty, from the historical charm of colonial Granada to the majesty of Masaya Volcano’s fuming crater to Carlos Pellas’ recently opened Mukul Resort—a modern splendor putting Nica on the map for global travelers in search of awesome luxury.

In a country that has weathered waves of promise and destruction, from its interoceanic heyday before the Panama Canal stole its thunder to its more recent damage from nearly a decade of civil war, hope radiates out of every devastating vista. And it’s no longer calling solely to ramblers and adventure seekers, though they’ll find plentiful options. Nica’s broad appeal—to the surfers, history buffs, eco conscious, cigar aficionados, jungle trekkers, and sybarites—has been here all along. It just wasn’t being offered on the right kind of plate. Why now? Because Carlos Pellas is in the kitchen.

It is to his credit that I’m here—Mukul’s February opening and the development at Guacalito de la Isla on Nica’s Emerald Coast are, mildly put, drawing attention. But this New York state-sized country is far greater than one man’s Pacific coast playground for the privileged. It’s a country only beginning to realize its potential.

The drive from the capital city of Managua to Granada offers 45 minutes of lush scenery down highway Carretera a Masaya, past the smoldering rim of the Masaya volcano. It’s not a leisurely drive, with sporadic, bleating beeps warding off weaving motorcycles, brave bicyclists, even bolder pedestrians, and cars drifting precariously across the lanes, but it makes the destination even dearer. We roll into the narrow streets, and crayon-hued facades of cerulean, atomic tangerine, and mint pop against the soupy evening sky. Mombacho Volcano’s graph-like outline divides the blue above the oldest city on the Central American continent.

Breakfast at La Gran Francia Hotel is in a garden surrounded by fragrant flowers tumbling over every surface, with basil so prolific that it looks more tree than herb. It’s this lushness, even in relative urbanity, that is one of Nica’s most striking qualities. Despite being sacked and burned numerous times, Granada has maintained its colonial charm, mostly due to a city law requiring that every building maintain the form of its original construction.

After a quick morning tour, we embark to the looming peak that dominates the Granada skyline. The 30-minute drive to the top of Mombacho Volcano begins as a steady ascent and turns clinging climb as we transition from one ecosystem to the next, marked by the shrill chirp of cicadas that sound like a car alarm on speed and helium, and the guttural roar of howler monkeys protecting their turf. This is volcano country, with vegetation stretching its massive arms in all directions. We make a pit stop at the midway visitors center and bistro of Café Las Flores—a local coffee company whose plantations scatter the hillsides—for a delicious jolt that rivals any precious cup in San Francisco.

On a hike bordering Mombacho’s safely passive crater, now a pit descending into an ombré of evergreens, our guide pauses to pick up a tuft of green—actually the smallest orchid in the world—and nestles it between the branches of a mossy tree. Such is the tender care with which the Nica people treat their land, their resources, their country. Our route takes us to the edge of a cliff overlooking Granada and its islets below—an outlook encircled by goldfish orchids leaping from the surrounding grasses.

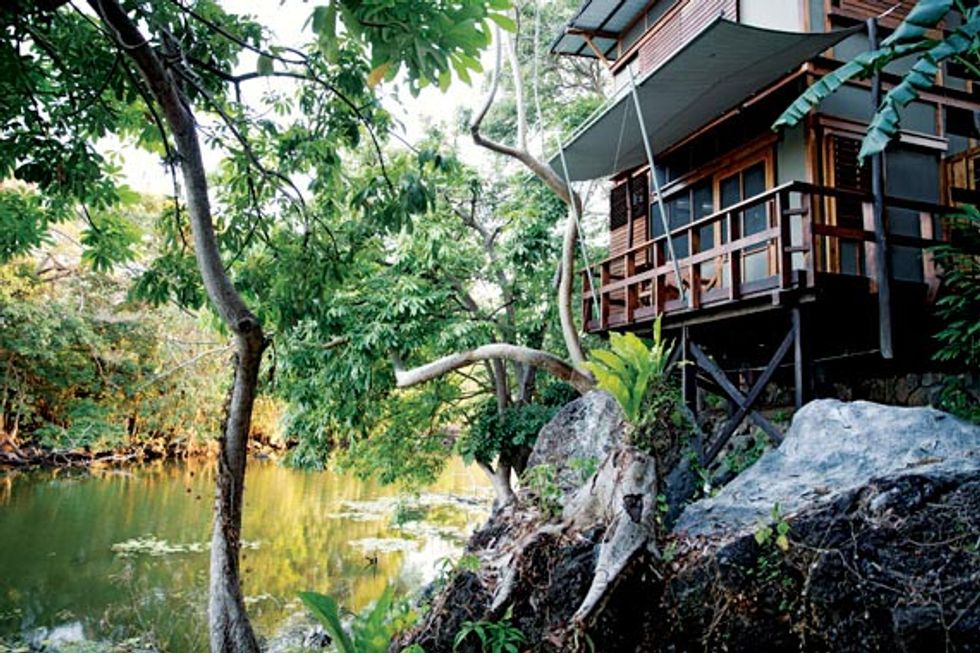

The howler monkeys seem to have followed us to Jicaro Island Ecolodge, the destination of the aforementioned boat ride, and engage in a twilight chorus with a radical refrain of birds. We arrive just in time to climb three flights of stairs up to the observation tower that offers views of the surrounding islets and Mombacho’s silhouette, which turns navy against the dense sky as the sun dips behind it. The night brings short relief from the heat with cooling winds off the lake, but it’s still warm enough to warrant a nighttime dip in the saltwater pool under a crescent moon. As the name might suggest, Jicaro waves the sustainable flag, offering minimum-impact lodging and employment opportunities for locals—of huge importance to one of the poorest countries in the Western Hemisphere (second only to Haiti). And while it may be a buzzword, the eco factor is one of the bigger draws for a stunning country attempting to slowly, carefully manage its touristic rise.

The approaching spike can be attributed in large part to Pellas’ Mukul. The rum and sugar magnate of Nicaragua is transforming the market with a development unlike any other in Central America. From the shores of Lake Nicaragua at San Jorge, it’s a 40-minute drive across verdant fields and scrubby hills, through the small town of Tola, and onto the newly paved road to Mukul. Ironically in parallel with Pellas’ in-progress project—phase two vacation homes are currently being built—the smooth ride stops abruptly, giving way to three miles of dirt road, past tin roof shacks that lean like weary travelers. And just as abruptly as the poverty sinks in, it gives way again to paved road and to guards standing at 20-foot gates, as if protecting the entrance to Oz.

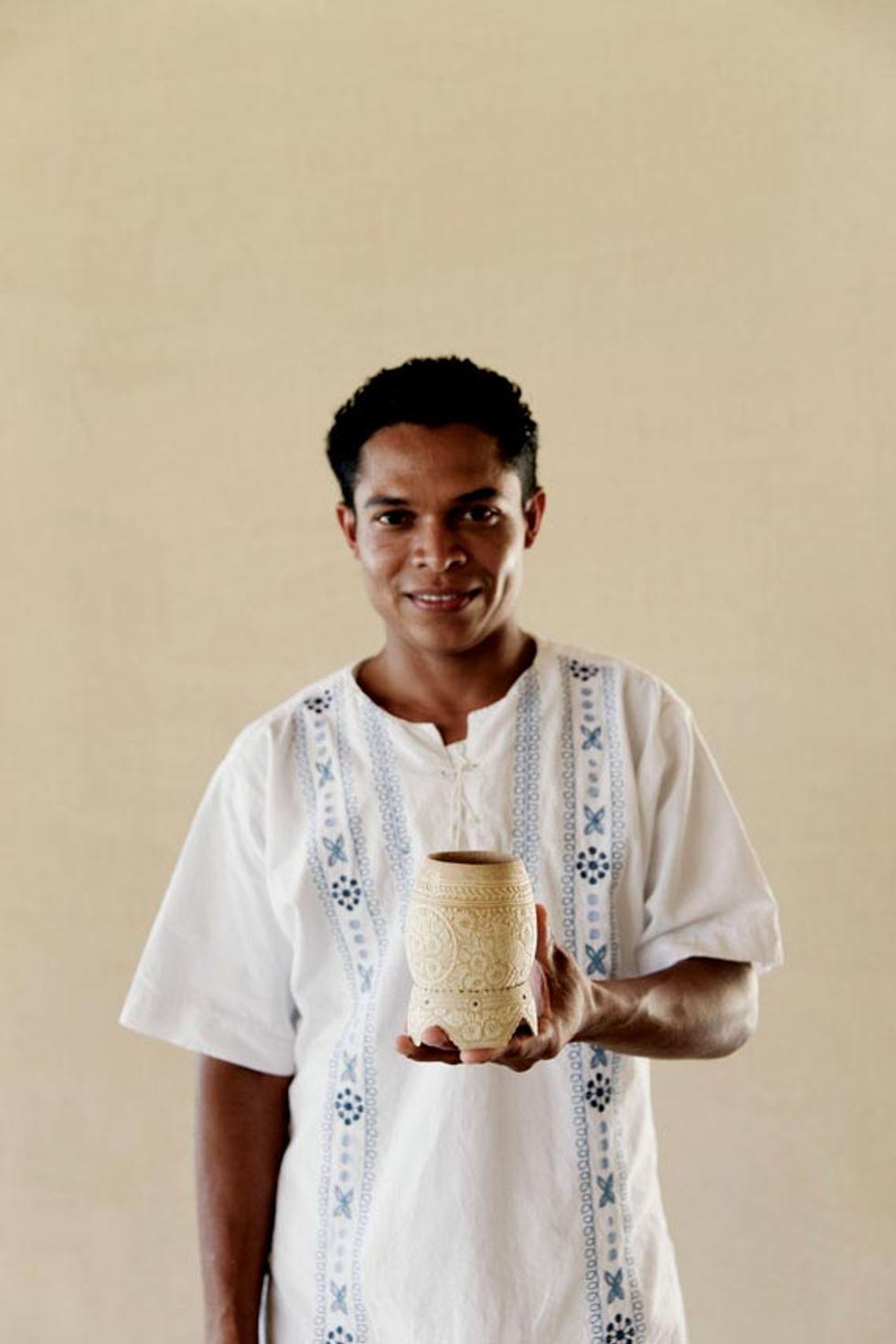

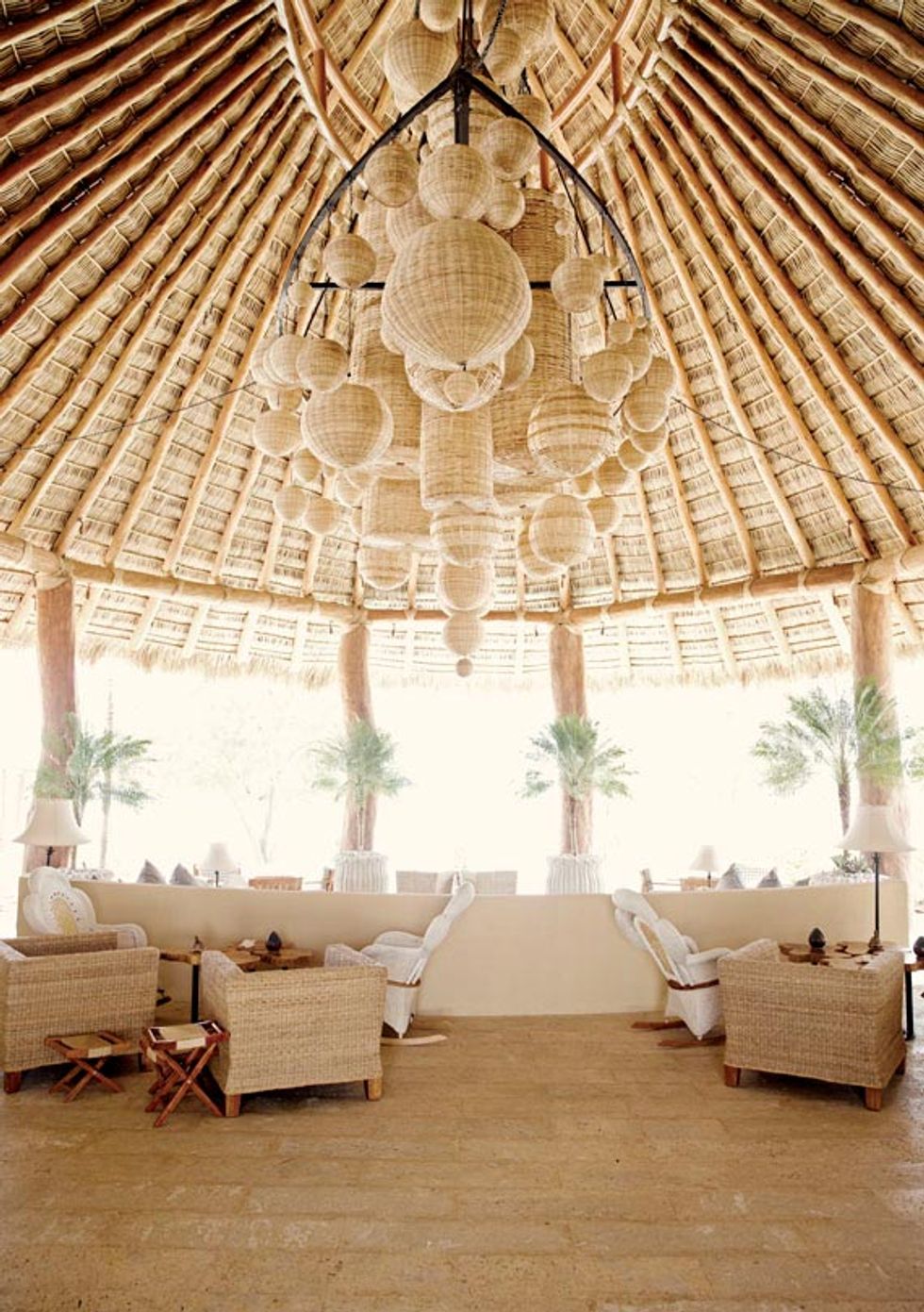

We descend into the Pellas kingdom, cradled by cliffs on either side of wide-open beach, the light matching our course and giving way to an electric smear of sunset. Our caravan arrives to the welcoming faces of beautiful locals, who speak delicately accented English, whisk our bags away, and guide us into a massive palapa—a thatched roof hut on the scale of what I imagine is like Dubai. In this plein-air lounge looking out upon the pool and beach beyond, an installation of lanterns—big, small, round, cylindrical—sway overhead in the breeze. They give a warm glow through their woven shells above a half-moon couch backed by gingham pillows made for giants. A cool, citrus-scented towel brings relief, though less so than the refreshing macuá—the national cocktail of Nica made from fresh orange, lemon, and guava juices, plus Flor de Caña rum (the Pellas family’s other business)—that’s delivered to our eager hands in a hand-carved jicaro cup.

Wonderfully luxurious, yes, but it’s the care and craft of the place, and its role in the surrounding community, that is most impressive. Dallas-based designer Paul Duesing’s interiors, rich with handcrafted details—carved teak tables, lamps made from the clay of Masaya Volcano—are composed of 90 percent Nicaraguan-made pieces, reflecting the country’s character, people, and resources. Rather than flying in well-trained hospitality professionals, Pellas hired locals, starting from scratch to train them how to work in a world that was previously foreign to them. English lessons are taught in a nearby school, offering a chance for the people, some of whom may live in the shanties we passed to get here, to drastically change their reality (a monthly salary can jump from $200 to $700 with proper training). “We ask that guests have patience—these people have lived through two wars. They’re shy,” says Claudia Silva, Mukul’s director of marketing and public relations. Shy perhaps, but endlessly lovely, as much if not more so than the scenery.

The spectacular hilltop Spa Mukul—really spas—strikes a personal tone: After surviving a plane crash in 1989, Pellas’ wife, Vivian, suffered burns on 40 percent of her body and 62 facial and bodily fractures. Inspired by her preference for privacy, the spa is comprised of six separate casitas (little thatched roof houses) with personal lockers, dressing rooms, treatment and outdoor lounge areas. Each is decked out with a different theme reflecting the offerings, from water therapy massages in the Rain Forest to indigenous healing practices using traditional plants grown on the property at Casita Mukul.

While savoring lobster risotto cooked in Flor de Caña and a rib-eye fit for a Viking on the patio, a sparsely tailed skunk meanders up the stairs from the beach to join us for dinner on our last night. “Welcome to Nicaragua,” says the manager, after uneventfully scooting him away from the kitchen and back the way he came—a reminder of the untamed nature of this place, despite its new polish.

This article was published in 7x7's May issue. Click here to subscribe.